![A cluster of type 3 cells (shown in green) in a mouse colon. These cells are induced by the microbiota and block type 2 allergic reactions. [Institut Pasteur]](https://genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/95320_web2549946126-1.jpg)

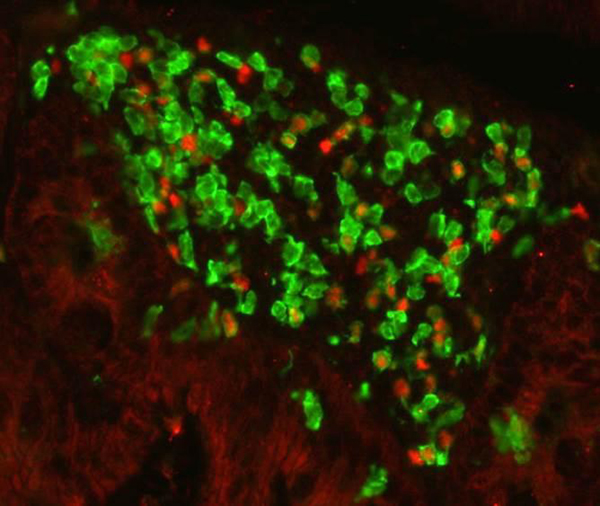

A cluster of type 3 cells (shown in green) in a mouse colon. These cells are induced by the microbiota and block type 2 allergic reactions. [Institut Pasteur]

The hygiene hypothesis has suggested a link between the decline of early exposure to infectious agents, symbiotic microorganisms, and even parasites, toward an increase in our susceptibility to allergic and autoimmune diseases, within industrialized countries.

Previous epidemiological studies have substantiated this hypothesis, by showing that children living in contact with farm animals—and by extension more microbial agents—developed fewer allergies during their lifetime. Conversely, laboratory studies have shown that administering antibiotics to mice within the first days of life results in a loss of microbiota, and subsequently, in an increased incidence in allergy.

Now, researchers from the Institut Pasteur have established a mechanism that explains the hygiene phenomena by demonstrating how the microbiota acts on the balance of the immune system. The investigators found that the presences of microbes specifically block a subset of immune cells that are responsible for triggering allergies.

The findings from this study were published recently in Science through an article entitled “The microbiota regulates type 2 immunity through RORγt+ T cells.”

Several types of immunological responses can be generated in order to defend the body from assault. The presence of bacterial or fungal microbes provokes a response from immune cells, known as type 3 cells—which coordinate the phagocytosis and killing of the microbial invaders. However, in the case of infection by pathogenic agents that are too large to be handled by type 3 cells (such as parasitic worms), the cells that organize the elimination of the pathogen, as well as allergic reactions, are known as type 2 cells.

The investigators showed that type 3 cells activated during a microbial aggression acted directly on type 2 cells and subsequently blocked their activity. As a consequence type 2 cells were unable to generate allergic immune responses. This effectively demonstrated that the microbiota indirectly regulates type 2 immune responses by inducing type 3 cells.

Interestingly, these results explain how an imbalance in the microbiota would trigger an exacerbated type 2 immune response leading to an allergic reaction.

“As we have evolved and develop in the presence of microbes, an absence of microbes leads to a loss in type 1 and type 3 responses, and therefore, to deregulated type 2 responses associated with pro-fibrotic and pro-allergic pathologies,” the scientists explained. “A similar mechanism may account for the increase, in industrialized nations, of autoimmune pathologies associated with type 3 immunity.”

These findings from the Pasteur scientists represent a critical step in understanding the exquisite balance between our various defense mechanisms. This data could also lead to new therapeutic approaches through the stimulation of type 3 cells by mimicking a microbial antigen in order to block allergy-causing type 2 cells.