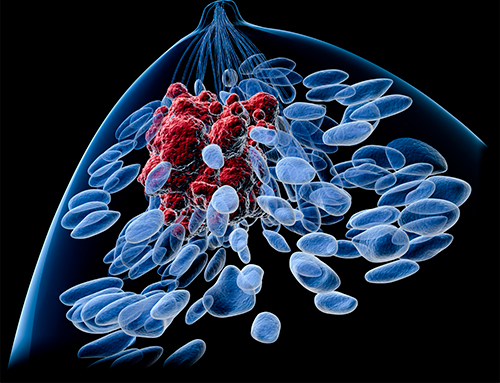

Researchers at the University of Basel and the University Hospital of Basel report a process that helps breast cancer cells implant themselves in certain places in the body. The findings suggest a way of preventing secondary tumors. Their study is published in The EMBO Journal in an article titled, “Nicotinamide N-methyltransferase sustains a core epigenetic program that promotes metastatic colonization in breast cancer.”

“Metastatic colonization of distant organs accounts for over 90% of deaths related to solid cancers, yet the molecular determinants of metastasis remain poorly understood,” wrote the researchers. “Here, we unveil a mechanism of colonization in the aggressive basal-like subtype of breast cancer that is driven by the NAD+ metabolic enzyme nicotinamide N-methyltransferase (NNMT). We demonstrate that NNMT imprints a basal genetic program into cancer cells, enhancing their plasticity.”

For eight years, a team led by Mohamed Bentires-Alj, PhD, professor of experimental surgical oncology University of Basel & University Hospital Basel, worked to establish the role of a cellular enzyme in breast cancer metastasis. The three lead authors Joana Pinto Couto, Milica Vulin, Charly Jehanno, and collaborators discovered a mechanism that appears to support metastasis in a range of aggressive cancers.

As the researchers learned through experiments on animals, overproduction of NNMT is key to metastasis. Overproduction of NNMT causes the cancer cells to also produce more collagen than normal.

It is known from previous studies that wandering cancer cells first have to find their way around in new tissues. The environment there—that is, the semiochemicals and available nutrients and oxygen—is different from that of the original tumor. In this preliminary stage of metastasis, the collagen in the new tissue helps the cancer cells survive and adapt.

What the new study found: particularly aggressively metastasizing breast cancer cells not only produce an excessive amount of NNMT, but also their own collagen. “This ability makes them less dependent on the collagen of the new tissue, so it’s even easier for the cancer cells to entrench themselves,” explained Jehanno.

“Next, we want to test whether existing NNMT inhibitors can also stop metastases in mouse models and whether they have any side effects,” explained Bentires-Alj. Following further development of NNMT targeting agents, the first studies in human patients could follow.