![Drug resistance can often emerge due to the selective pressure of antibiotic use on a microbial population. [NIAID]](https://genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/5081362184_6fee0ef73a_z7070611931-1.jpg)

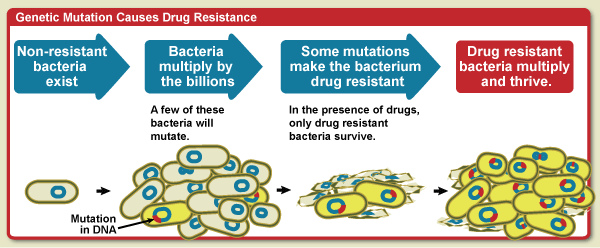

Drug resistance can often emerge due to the selective pressure of antibiotic use on a microbial population. [NIAID]

Until recently, resistance to the polymyxin class of antibiotics—the last line of microbial defense—was thought to be highly improbable. However now, Chinese scientists have discovered a new gene, called mcr-1 that is widespread among Enterobacteriaceae, a large family of Gram-negative bacteria that include a variety of human pathogens, after taking samples from pigs and patients in South China.

“These are extremely worrying results. The polymyxins (colistin and polymyxin B) were the last class of antibiotics in which resistance was incapable of spreading from cell to cell. Until now, colistin resistance resulted from chromosomal mutations, making the resistance mechanism unstable and incapable of spreading to other bacteria,” explained co-author Jian-Hua Liu, Ph.D., a professor at the South China Agricultural University in Guangzhou, China. “Our results reveal the emergence of the first polymyxin resistance gene that is readily passed between common bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, suggesting that the progression from extensive drug resistance to pandrug resistance is inevitable.”

The investigators found the mcr-1 gene on plasmids within various bacterial strains, suggesting an alarming potential to spread and differentiate between diverse microbial populations.

The findings from this study were published recently in The Lancet Infectious Diseases through an article entitled “Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study.”

The researchers stumbled across the mcr-1 gene while performing routine testing of livestock for antimicrobial resistance on a pig farm in Shanghai. This prompted the researchers to collect bacteria samples from pigs at slaughter across four provinces, and from pork and chicken sold in 30 open markets and 27 supermarkets across Guangzhou between 2011 and 2014. Additionally, the scientists analyzed bacteria samples from patients presenting with infections at two hospitals in Guangdong and Zhejiang provinces.

What they found was troubling to say the least, as a high prevalence of the mcr-1 gene in E. coli was observed in isolates from animal (166 of 804) and raw meat samples (78 of 523). Moreover, the proportion of positive samples has been observed to be increasing from year to year.

The scientists also found that the transfer rate of the mcr-1 gene was very high between E. coli strains and that it has a strong potential to spread into other epidemic pathogenic bacterial species such as K. pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa—making the rapid dissemination into humans very likely.

“Because of the relatively low proportion of positive samples taken from humans compared with animals, it is likely that mcr-1 mediated colistin resistance originated in animals and subsequently spread to humans,” noted senior author Jianzhong Shen, Ph.D., professor at the China Agricultural University in Beijing, China. “The selective pressure imposed by increasingly heavy use of colistin in agriculture in China could have led to the acquisition of mcr-1 by E. coli.”

The importance of selective pressure on this resistance gene becomes even more evident when considering the fact that China is one of the world's largest users and producers of colistin for agriculture and veterinary use. Worldwide, the demand for colistin in agriculture is expected to reach almost 12,000 tons per year by the end of 2015, rising to 16,500 tons by 2021.

“The emergence of mcr-1 heralds the breach of the last group of antibiotics,” the authors stated. “Although currently confined to China, mcr-1 is likely to emulate other resistance genes such as blaNDM-1 and spread worldwide. There is a critical need to re-evaluate the use of polymyxins in animals and for very close international monitoring and surveillance of mcr-1 in human and veterinary medicine.”