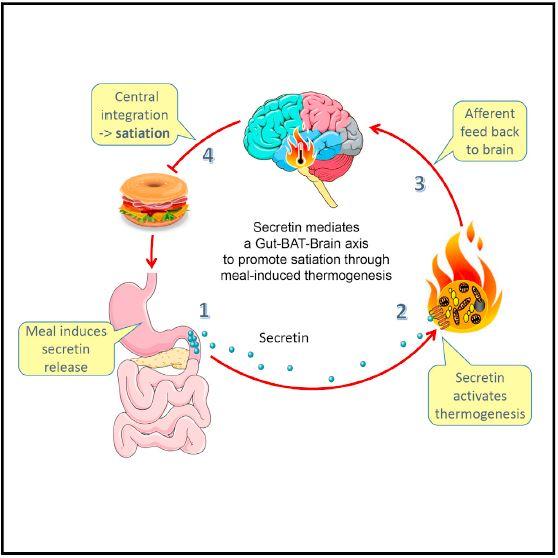

Scientists from Germany and Finland report that brown fat interacts with the gut hormone secretin in mice to relay nutritional signals about fullness to the brain during a meal. The study (“Secretin-Activated Brown Fat Mediates Prandial Thermogenesis to Induce Satiation”), published in Cell, reinforces our understanding of a long-suspected role of brown adipose tissue, a type of body fat known to generate heat when an animal is cold, in the control of food intake, according to the researchers.

“The molecular mediator and functional significance of meal-associated brown fat (BAT) thermogenesis remains elusive. Here, we identified the gut hormone secretin as a non-sympathetic BAT activator mediating prandial thermogenesis, which consequentially induces satiation, thereby establishing a gut-secretin-BAT-brain axis in mammals with a physiological role of prandial thermogenesis in the control of satiation. Mechanistically, meal-associated rise in circulating secretin activates BAT thermogenesis by stimulating lipolysis upon binding to secretin receptors in brown adipocytes, which is sensed in the brain and promotes satiation. Chronic infusion of a modified human secretin transiently elevates energy expenditure in diet-induced obese mice,” wrote the investigators.

“Clinical trials with human subjects showed that thermogenesis after a single-meal ingestion correlated with postprandial secretin levels and that secretin infusions increased glucose uptake in BAT. Collectively, our findings highlight the largely unappreciated function of BAT in the control of satiation and qualify BAT as an even more attractive target for treating obesity.”

“We demonstrate a connection between the gut, the brain, and brown tissue, uncovering a previously unknown facet of the complex regulatory system controlling energy balance,” said lead author Martin Klingenspor, Ph.D., chair of molecular nutritional medicine at the Technical University of Munich. “The view of brown fat as a mere heater organ must be revised, and more attention needs to be directed towards its function in the control of hunger and satiation.”

During a meal, signals encoded by gut hormones reach the brain via the blood or through nerves activated in the small intestine. The work by Klingenspor and colleagues indicates that the gut hormone secretin—first recognized in 1902 to stimulate the pancreas to secrete bicarbonate to help the small intestine neutralize acid and digest macronutrients—has an underappreciated role in satiation.

In their study, hungry mice that were injected with secretin had suppressed appetites. Injecting mice with secretin also increased the amount of heat that their brown fat produced. Mice with inactivated brown fat tissue, however, didn’t experience the same appetite suppression when they were injected with the hormone, suggesting that it is secretin’s effect on BAT that causes the feeling of fullness.

In addition to studying the effects of secretin on brown fat in mice, secretin levels were measured in 17 human volunteers. In a study in Finland, brown-tissue oxygen consumption and fatty-acid uptake were measured in participants’ blood after overnight fasting and 30–40 minutes after a meal. Researchers found that higher levels of secretin in the subjects’ blood corresponded to more metabolically active brown fat.

Dr. Klingenspor says that one day, we may know enough about the secretin-brown fat connection to stimulate secretin production by eating certain foods. “Any stimulus that activates brown fat thermogenesis could potentially induce satiation,” he said. “Secretin secretion is sensitive to nutrients, so eating the right starter could be helpful in promoting satiation and result in reduced meal size and caloric intake.”

He believes that brown fat’s roles in controlling hunger and satiation make it a particularly attractive target for new approaches to treating obesity. Targeting brown fat through secretin might hold promise for potential future nutritional or pharmacological interventions against obesity and metabolic disease, he said.