The immune system is incredibly efficient at targeting bacterial pathogens when they enter into the human body to colonize and set up infection. Given that, how does the immune system deal with the hundreds of different species of bacteria that have set up a long-term residence as members of the microbiome?

Scientists have long suspected that the gut’s immune system, in the face of so many stimuli, takes an uncharacteristically blunt approach to population control. But now, new research suggests that the gut’s local immune system is precise, creating antibodies that appear to home in on specific microbiota.

This work is published in Nature in the paper, “Tunable dynamics of B cell selection in gut germinal centers.”

“It was thought that the gut immune system worked sort of like a general-purpose antibiotic, controlling every bug and pathogen,” said Gabriel Victora, PhD, an assistant professor at the Rockefeller University. “But our new findings tell us that there might be a bit more specificity to this targeting.”

The research suggests that our immune system may play an active part in shaping the composition of our microbiomes, which are tightly linked to health and disease. “A better understanding of this process could one day lead to major implications for conditions where the microbiome is knocked out of balance,” said Daniel Mucida, PhD, associate professor at the Rockefeller University.

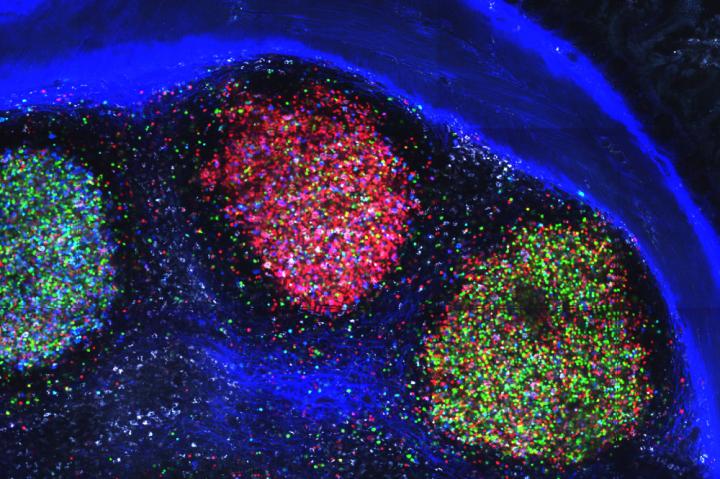

Germinal centers are the structures in the body where B cells evolve to produce antibodies with high affinity for various antigens. These usually form transiently in lymphoid organs in response to infection or immunization.

However, in lymphoid organs associated with the gut, germinal centers are chronically present, supporting antibody responses to gut infections.

Victora, Mucida, and colleagues set out to study how these B cells interact with the melting pot of bacterial species in the gut—an overabundance of potential targets. The group combined “multicolor ‘Brainbow’ cell-fate mapping and sequencing of immunoglobulin genes from single cells.” They found that 5–10% of gut-associated germinal centers from specific-pathogen-free (SPF) mice contain highly dominant ‘winner’ B cell clones at steady state, despite rapid turnover of germinal-center B cells.

They then homed in on the winning B cells and found that their antibodies were indeed designed to bind with ever increasing potency to specific species of bacteria living in the gut. More specifically, the monoclonal antibodies derived from these clones “show increased binding, compared with their unmutated precursors, to commensal bacteria, consistent with antigen-driven selection.”

The findings show that even in the gut, where millions of microbes have antigens and vie for the immune system’s attention, germinal centers manage to select specific, consistent winners.

“We can now investigate the winners and look at evolution in germinal centers as an ecological issue involving many different species, as we try to figure out the rules underlying selection in these complex environments,” Victora said. “This opens up a whole new area of inquiry.”