Gut organoids, three-dimensional cell culture models of the intestine, have been used to demonstrate that the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 can infect cells of the intestine and multiply there. The models indicate that SARS-CoV-2 might also infect and replicate in the cells lining the human intestine. It is even possible that the human intestine is—as researchers have suspected—a significant route for SARS-CoV-2 transmission. That is, SARS-CoV-2 transmission via gastrointestinal organs, as well as that via the respiratory organs, may account for the devastating spread of COVID-19.

Patients with COVID-19 show a variety of symptoms associated with respiratory organs—such as coughing, sneezing, shortness of breath, and fever—and the disease is transmitted via tiny droplets that are spread mainly through coughing and sneezing. One-third of the patients, however, also have gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea and diarrhea. In addition, the virus can be detected in human stool long after the respiratory symptoms have been resolved. This suggests that the virus can also spread via so-called fecal-oral transmission.

Though the respiratory and gastrointestinal organs may seem very different, there are some key similarities. A particularly interesting similarity is the presence of the ACE2 receptor, the receptor through which the COVID-19 causing SARS-CoV-2 virus can enter the cells. The inside of the intestine is loaded with ACE2 receptors. However, it has been unclear whether intestinal cells could get infected and produce virus particles.

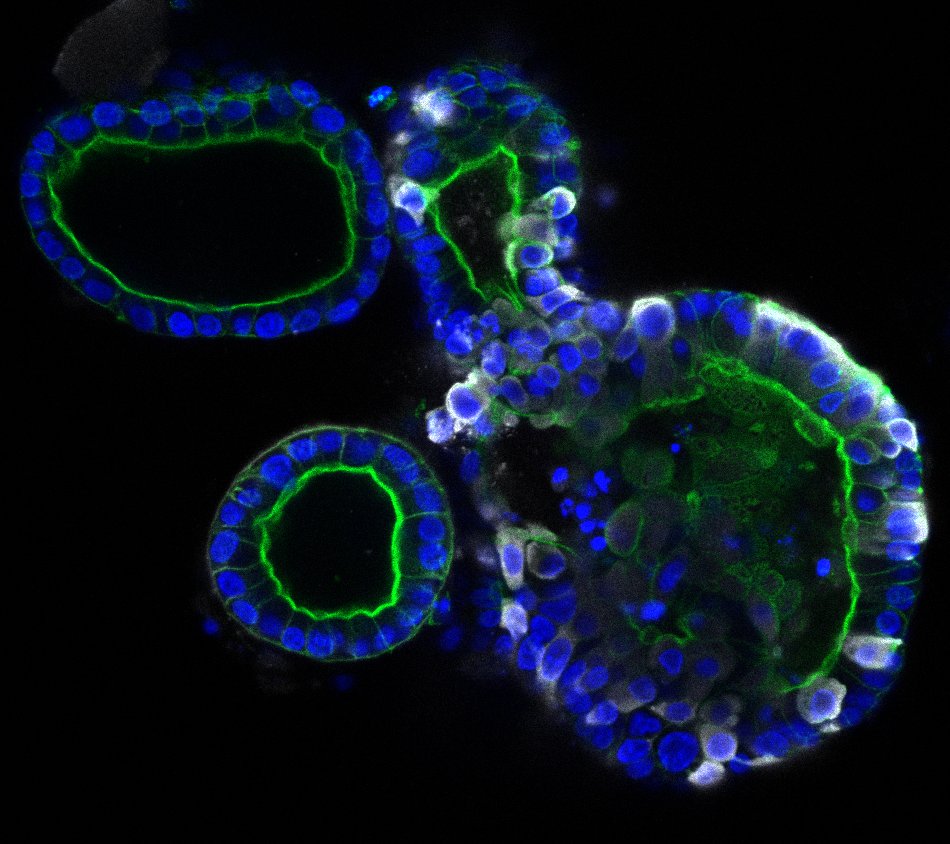

To explore the possibility of an intestinal route, scientists in the Netherlands generated human small intestinal organoids (hSIOs) derived from primary gut epithelial stem cells. The scientists—who represented—Hubrecht Institute, Erasmus University Medical Center, and Maastricht University—asserted that such hSIOs contain all the proliferative and differentiated cell types of the in vivo epithelium.

When grown in four different culture conditions, the hSIOs contained cells that expressed varying amounts of ACE2 and were thus capable, in theory, of being infected with SARS-CoV-2. To see if the cells actually experienced infection, the scientists observed them closely, as described in an article (“SARS-CoV-2 productively infects human gut enterocytes”) that appeared May 1 in the journal Science.

“In hSIOs, enterocytes were readily infected by SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 as demonstrated by confocal and electron microscopy,” the article’s authors wrote. “Consequently, significant titers of infectious viral particles were detected. mRNA expression analysis revealed strong induction of a generic viral response program.”

Essentially, the scientists discovered that the virus infected both mature and progenitor enterocytes, which are intestinal absorptive epithelial cells that line the inner surface of the intestines. The scientists also found that the virus provoked the activity of genes involved with antiviral responses. Notably, the rates of infection were similar across the organoid models, indicating that even low quantities of ACE2 may be enough for the virus to infect epithelial cells.

“The observations made in this study provide definite proof that SARS-CoV-2 can multiply in cells of the gastrointestinal tract,” said Bart Haagmans, PhD, a corresponding author of the current study and a researcher at Erasmus University Medical Center. “However, we don’t yet know whether SARS-CoV-2, present in the intestines of COVID-19 patients, plays a significant role in transmission. Our findings indicate that we should look into this possibility more closely.”

The current study is in line with other recent studies that identified gastrointestinal symptoms in a large fraction of COVID-19 patients and virus in the stool of patients free of respiratory symptoms. Special attention may be needed for those patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. More extensive testing using not only nose and throat swabs, but also rectal swabs or stool samples may thus be needed.

In the meantime, the researchers are continuing their collaboration to learn more about COVID-19. They are studying the differences between infections in the lung and the intestine by comparing lung and intestinal organoids infected with SARS-CoV-2.