Studies by scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute showed that feeding mice with two prebiotics, mucin and inulin, boosted the immune system’s ability to fight cancer, slowed the growth of implanted melanoma tumors, and delayed the development of resistance to established drugs. The anticancer effects of the two prebiotics were linked with changes in the composition of the animals’ gut microbial communities, which induced antitumor immune responses. The researchers say their study, published in Cell Reports, provides further evidence for the role that gut microbes play in shaping the immune response to cancer, and supports efforts to target the gut microbiome as an approach to enhancing the efficacy of cancer therapy.

“Prebiotics represent a powerful tool to restructure gut microbiomes and identify bacteria that contribute to anticancer immunity,” said Scott Peterson, PhD, professor in Sanford Burnham Prebys’ Tumor Microenvironment and Cancer Immunology Program and co-corresponding author of the study. “The scientific advances we are making here are getting us closer to the idea of implementing prebiotics in cutting-edge cancer treatments.” Peterson and colleagues reported their studies in a paper titled, “Prebiotic-Induced Anti-tumor Immunity Attenuates Tumor Growth.”

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract harbors a complex, dynamic population of bacteria that are implicated in the maintenance of health, the onset or progression of disease, and which affect key aspects of homeostasis and physiology, including the development and function of the immune system, the authors explained. Gut microbiota also influence the progression of some cancers in model systems. “Changes in gut microbiota composition are linked to local and systemic alterations that affect tumor growth, in part through modulation of tissue remodeling, mucosal immunity, and antitumor immunity,” the team continued.

In contrast with probiotics, which are live bacterial strains, prebiotics such as inulin and mucin act as food for bacteria, and stimulate the growth of diverse beneficial microbial populations. Mucin is a protein that makes up part of the mucus found in the intestine, while inulin is a fiber that is found in plants such as asparagus and onions.

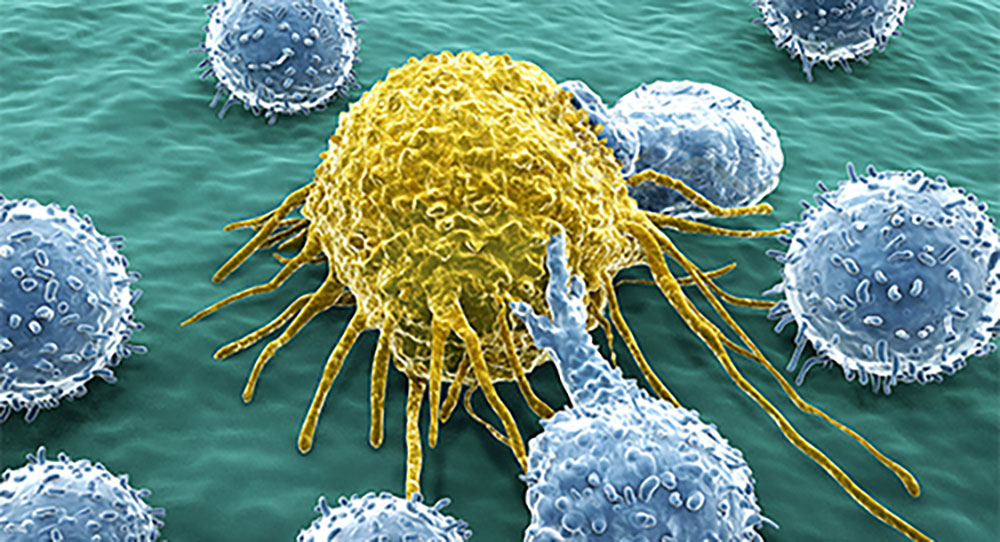

Laboratory studies have suggested that these two prebiotics may boost the abundance of bacterial species that can help to suppress tumor growth. For their reported studies, the researchers undertook a series of experiments in which mice fed inulin and/or mucin as part of their diets were transplanted with melanoma or colon cancer cells to determine the effects of the prebiotics. Their initial findings in melanoma-implanted mice showed that prebiotic supplementation induced “a shift to a proinflammatory tumor microenvironment,” which was associated with a more potent antitumor response. Further analyses indicated that the prebiotics impacted on both innate and adaptive immune cells, including activating T cells, and altering the expression of chemokines, inflammasome-related genes, and antigen presentation-related genes.

The in vivo experiments showed that growth of melanoma was slowed in the mice that were fed either mucin or inulin, while growth of a colon cancer cell line was slowed in mice that received dietary inulin. Mice with melanoma that received either of the two prebiotics showed an increase in the proportion of immune system cells that had infiltrated the tumor, indicating that the prebiotics enhanced the immune system’s ability to attack the cancer.

Gut microbiome communities were also differentially altered in the mice that received either mucin or inulin. Importantly, each of the prebiotics was linked with the creation of different bacterial populations, both of which were able to stimulate antitumor immunity. “We found that both inulin and mucin effectively limited the growth of melanoma cells, but they elicited distinct phenotypes that are likely to stem from their differential effects on gut microbiota,” the team noted. “These findings suggest that inulin and mucin drive distinct changes in gut microbiota, both of which are capable of inducing antitumor immunity … The immunomodulatory effects of the two prebiotics were largely overlapping but not identical, and had similar effects on tumor control.”

Melanoma is one of the most aggressive tumor types, and has a propensity to metastasize and resist therapy, the authors commented. Aberrant activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway has been reported in human tumors with mutant BRAF and NRAS, including melanomas, “in which they account for more than 70% of genetic changes.” One approach to treating such tumors is the use of inhibitors of the MAPK pathway, including MEK inhibitors (MEKi), and these are commonly used for treating NRAS mutant melanomas. However, co-author Jennifer Wargo, MD, associate professor of surgical oncology and genomic medicine at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, commented, “Immunotherapies and targeted treatments such as MEK inhibitors are helping people with melanoma, but not everyone. While some patients respond to therapy, others do not. In addition, many patients develop resistance to treatment, which requires alternate medicine combinations.”

The reported studies showed that feeding inulin to mice carrying NRAS-mutant melanomas resulted in delayed development of resistance to MEK inhibitor therapy. “… co-administration of MEKi with inulin had an additive effect on tumor growth control, and the emergence of MEKi resistance was delayed compared with MEKi alone, implying that MEKi resistance may be partially overcome by this probiotic,” the scientists stated. “Manipulating the microbiome with prebiotics might be a helpful addition to current treatment regimens, and today’s finding should be further tested in independent models and systems,” Wargo noted.

The scientists concluded that their findings represent “a paradigm for control of tumor growth by gut microbiota by demonstrating that taxa from multiple unrelated phylogenetic groups share the capacity to induce antitumor immunity.” The collective results, in addition, represent a step forward in understanding how certain prebiotics affect tumor growth, although there remains a long way to go before clinical application can be considered, commented Ze’ev Ronai, PhD, professor in Sanford Burnham Prebys’ Tumor Initiation and Maintenance Program and senior author of the study. “Earlier studies have demonstrated that prebiotics limit tumor growth, but until now the mechanism by which they do so has been unclear … Our study shows for the first time that prebiotics limit cancer growth by enhancing antitumor immunity. The study supports further exploration of the potential benefits of prebiotics in treating cancer or augmenting current therapies. Future studies need to be conducted in more complex animal models of different genetic backgrounds and ages to address the complex nature of human tumors before we may consider evaluating these prebiotics in people.”

As the researchers stated, “It is expected that refinement of the specific bacterial strains and metabolites that mediate these phenotypes will not only advance our understanding of the phenomenon but also facilitate the development of therapeutic modalities that could be tested across species.”