![Micrographs of newly described membranes vesicles that induce autoantibody production and accelerate rejection are shown. [Université de Montréal, CRCHUM]](https://genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Dec17_2015_CRCHUM_MicrographsMembranes4722041081-1.jpg)

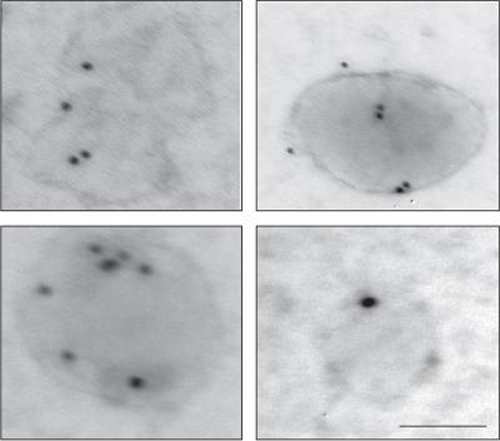

Micrographs of newly described membranes vesicles that induce autoantibody production and accelerate rejection are shown. [Université de Montréal, CRCHUM]

Scientists at the University of Montreal Hospital Research Centre (CRCHUM) say they have found a new cellular structure responsible for previously unexplained rejection of organ transplants. They believe their discovery could one day revolutionize transplantation practice by modifying risk assessment of rejection in people who receive heart, lung, kidney, or liver transplants.

“We have found the mechanism that makes patients react against components of their own blood vessels even before receiving an organ transplant, and we have identified a drug that can prevent this type of rejection,” said Marie-Josée Hébert, M.D., a transplant physician and researcher at the CRCHUM and a professor in the university's department of medicine. The team’s study (“The 20S proteasome core, active within apoptotic exosome-like vesicles, induces autoantibody production and accelerates rejection”) findings is published in Science Translational Medicine

Rejection is always a risk of transplantation. The phenomenon is usually caused by a reaction of the recipient's immune system vis-à-vis the transplant, when it “detects” an invader. Human leucocyte antigens serve as a unique identifier for each person. In transplants, doctors try to avoid rejection by ensuring that the donor and recipient are compatible with regard to blood group and HLA antigens. Despite these precautions, one in ten transplants results in rejection.

To solve this mystery, the researchers focused on blood vessels which, when damaged, make rejection more difficult to treat. “We discovered that the damaged blood vessels release specific bits of cells: small membrane vesicles that put the immune system on alert. If we then perform a transplant, the immune system immediately attacks the donor organ,” noted Melanie Dieudé, Ph.D., a researcher at the CRCHUM and first author of the study.

The tiny vesicles derive from dying cells and produce autoantibodies. “In addition to the immune system reacting against HLAs, it surprisingly reacts against components of our own cells. So rejection is not simply a reaction against another person, it is also a reaction against elements that belong to us,” added Dr. Hébert, who is also co-director of the Canadian National Transplant Research Program.

Dr. Hébert's team has found a way to neutralize the enzyme driver of these small vesicles (proteasomes) through a drug, bortezomib, currently used to treat certain bone marrow cancers. Bortezomib has the effect of making the immune system deaf to alerts. Results from cultured cells and animal models are promising, and a clinical study in humans is ongoing, according to Dr. Hébert.

“If a recipient has already reacted to these small vesicles and receives an organ that is also in the process of releasing vesicles, it is probably a dangerous situation. This is what we are still examining,” explained Dr. Hébert.