Scientists at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) say they have found a way to target drug-resistant esophageal cancer cells by exploiting the different energy needs of cancerous versus healthy cells. The team, whose study (“Targeting glutamine-addiction and overcoming CDK4/6 inhibitor resistance in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma”) appears in Nature Communications, believes their findings open the doorway to new treatments for an otherwise lethal cancer.

“The dysregulation of Fbxo4-cyclin D1 axis occurs at high frequency in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), where it promotes ESCC development and progression. However, defining a therapeutic vulnerability that results from this dysregulation has remained elusive. Here we demonstrate that Rb and mTORC1 contribute to Gln-addiction upon the dysregulation of the Fbxo4-cyclin D1 axis, which leads to the reprogramming of cellular metabolism,” the investigators wrote.

“This reprogramming is characterized by reduced energy production and increased sensitivity of ESCC cells to combined treatment with CB-839 (glutaminase 1 inhibitor) plus metformin/phenformin. Of additional importance, this combined treatment has potent efficacy in ESCC cells with acquired resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors in vitro and in xenograft tumors. Our findings reveal a molecular basis for cancer therapy through targeting glutaminolysis and mitochondrial respiration in ESCC with dysregulated Fbxo4-cyclin D1 axis as well as cancers resistant to CDK4/6 inhibitors.”

Only about 20% of patients diagnosed with ESCC are still alive five years later, according to the American Cancer Society. Unfortunately, this disease is usually found at a late or advanced stage, meaning that, for many patients with ESCC, the cancer has already spread to other parts of their bodies. The severity of the disease is compounded by its high rate of recurrence.

“It’s an aggressive, lethal cancer,” said Shuo Qie, MD, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at MUSC Hollings Cancer Center and first author on the article. “Surgery is the only and the best choice. But some patients, especially patients with metastasis, need chemotherapy or other additional treatments.”

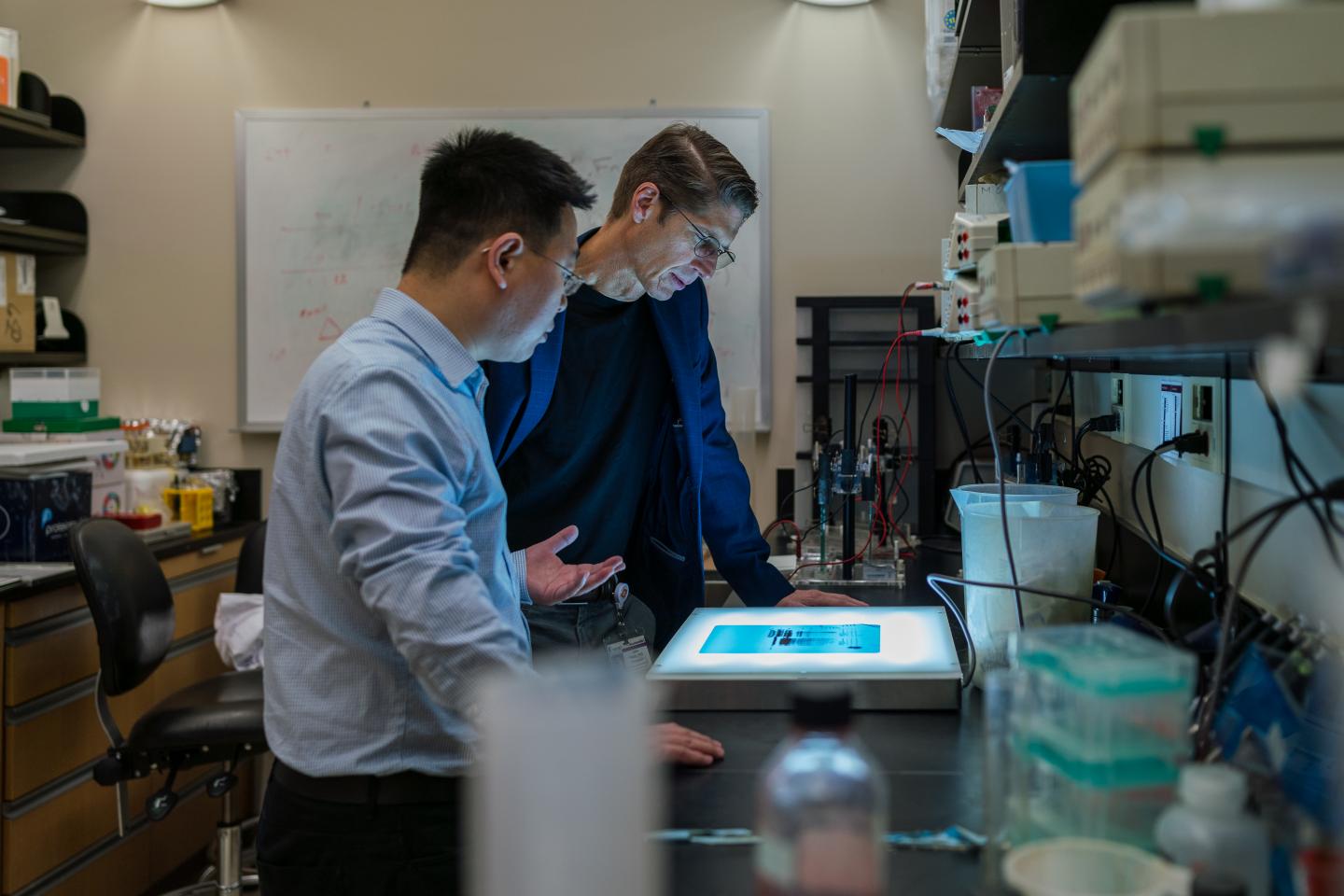

For the study, Qie aimed to further characterize and ideally address the cancer-driving pathway previously discovered by J. Alan Diehl, PhD, his mentor and the senior author on the article. Diehl is the SmartState endowed chair in lipidomics and pathobiology and associate director of basic science at MUSC Hollings Cancer Center.

This pathway, the Cyclin D1 axis, is an intersection at which several cancer-promoting changes occur. The protein Fbxo4, which usually prevents cancer by controlling cyclin D1 degradation, no longer exerts its protective effects. This allows cells to spiral out of control.

Qie discovered that the axis activates a metabolic switch that causes ESCC cells to depend much more on glutamine than glucose. Healthy cells break down both glucose and glutamine for their energy needs, but ESCC cells are virtually addicted to glutamine.

“The cancer cells have to have glutamine. You can bathe them in glucose and they’re still going to die without glutamine,” explained Diehl.

These findings point to a vulnerability in these cancer cells and suggest a new therapeutic possibility—the use of glutaminase inhibitors. Glutaminase is an enzyme required for the cellular digestion of glutamine. Inhibiting it effectively blocks the cell’s ability to process glutamine.

The MUSC researchers tested the efficacy of a combination regimen that included a glutaminase inhibitor (Telaglenastat; Calithera, San Francisco, CA) and metformin in cancer cell lines and mice. They found that the combination regimen effectively treated tumors with the molecular signature that Diehl had previously described.

Importantly, the treatment was effective even against tumors that had developed resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors. Indeed, the resistant cancer cells were even more vulnerable to this treatment than non-resistant ones.

“It’s quite remarkable that the tumor cells that we have that are resistant to CDK4/6 inhibitors are actually five-, six-fold more sensitive to this combination therapy than they were before they developed resistance,” said Diehl.

The findings for this combination regimen in both cellular and animal models suggest that it could have therapeutic potential for patients diagnosed with this traditionally dangerous and difficult cancer. Having moved this treatment from concept to reality in the laboratory, Qie and Diehl hope to move forward with clinical trials for their combination treatment and are currently seeking funding to do so.

The MUSC researchers’ curiosity about a biological pathway has led to a potential new therapeutic approach for patients with ESCC.

“You’ll hear the term ‘an Achilles heel,'” explained Diehl. “Can you find the Achilles heel that’s in the cancer but not in the normal cell? And that’s what Qie has done. Just from trying to understand the biology of the pathway, he and I have identified a unique therapeutic opportunity.”