Scientists from the Instituto de Medicina Molecular (iMM) Lisboa in Portugal say they and collaborators have created a chimeric virus that allows them to study novel approaches to treat cancer caused by human herpesvirus infection in a mouse model.

Herpes simplex, chickenpox, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr, and Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus infect humans for life and can cause cancer in some people. Cancers associated with Kaposi virus infection are dependent on the survival of the virus. If the virus can be eliminated, cancer cells would no longer proliferate.

In collaboration with Harvard Medical School, a team led by iMM's Pedro Simas, Ph.D., and Kenneth Kaye, M.D., from Harvard, studied a Kaposi virus protein vital for maintaining infection named LANA, or latency-associated nuclear antigen, without which the virus can't cause cancer.

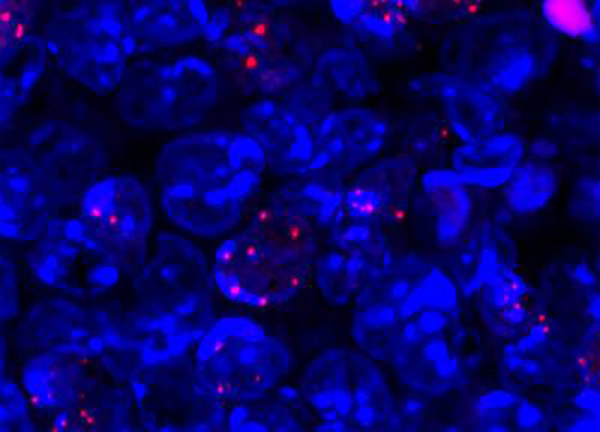

“Many pathogens, including Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV), lack tractable small animal models. KSHV persists as a multi-copy, nuclear episome in latently infected cells. KSHV latency-associated nuclear antigen (kLANA) binds viral terminal repeat (kTR) DNA to mediate episome persistence. Model pathogen murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV68) mLANA acts analogously on mTR DNA. kLANA and mLANA differ substantially in size and kTR and mTR show little sequence conservation,” write the investigators whose study (“Cross-Species Conservation of Episome Maintenance Provides a Basis for In Vivo Investigation of Kaposi's Sarcoma Herpesvirus”) appears in PLOS PATHOGENS. “Here, we find kLANA and mLANA act reciprocally to mediate episome persistence of TR DNA. Further, kLANA rescued mLANA deficient MHV68, enabling a chimeric virus to establish latent infection in vivo in germinal center B cells. The level of chimeric virus in vivo latency was moderately reduced compared to WT infection, but WT or chimeric MHV68 infected cells had similar viral genome copy numbers as assessed by immunofluorescence of LANA intranuclear dots or qPCR. Thus, despite more than 60 Ma of evolutionary divergence, mLANA and kLANA act reciprocally on TR DNA, and kLANA functionally substitutes for mLANA, allowing kLANA investigation in vivo. Analogous chimeras may allow in vivo investigation of genes of other human pathogens.”

The researchers discovered that when LANA is cloned into a virus similar to Kaposi, but which only infects mice, it remains functional. According to the scientists, this was a surprising finding because they thought that due to the evolutionary divergence between human and other animal viruses, the genes that code for LANA could not be switched. But their study clearly demonstrates that despite more than 60 million years of evolutionary divergence between the human Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus and its rodent homolog, LANA's functional mechanisms are preserved.

The team says its chimeric virus (a mouse virus with a human viral gene) can be used to test molecules that inhibit human LANA protein in an animal model of disease, treating not only human herpesvirus infection but also its associated cancers. The goal is to ultimately use these molecules as drugs to treat Kaposi virus–associated lymphomas.

“In addition to Kaposi virus, the same experimental strategy to create chimera viruses, previously thought to be theoretically nonviable, can now be used for other viruses that use proteins similar to LANA, such as the Epstein-Barr virus, which infects greater than 90% of the world population, or the human papillomavirus responsible for cervical cancers,” said Dr. Simas.