![Brain scan from a trial patient showing significant shrinkage of the tumor. [Clinical Cancer Research/American Association for Cancer Research]](https://genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/137985_web2306916335-1.jpg)

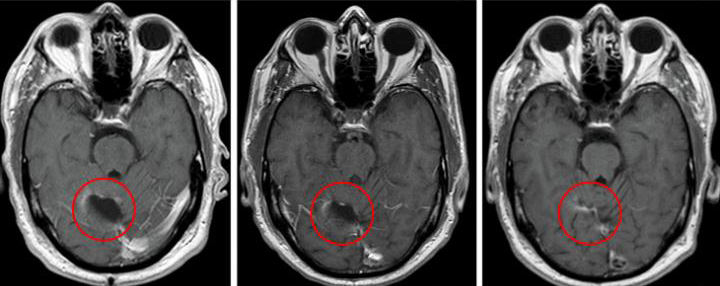

Brain scan from a trial patient showing significant shrinkage of the tumor. [Clinical Cancer Research/American Association for Cancer Research]

Multipronged strategies have been effective approaches in a variety scenarios—combat, sales, end even politics. Medicine is no stranger to these sorts of tactics; however, finding the right efficacious combination to treat disease or improve a patient’s quality of life is no simple task. Yet now, investigators at the Duke Cancer Institute may have just hit pay dirt with a new combination therapy for a particularly aggressive form of brain cancer—glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). The findings from a Phase I study involving 11 patients with GBM, who received injections of an investigational vaccine therapy combined with an approved chemotherapy drug, were published today in Clinical Cancer Research in an article entitled “Long-term Survival in Glioblastoma with Cytomegalovirus pp65-Targeted Vaccination.”

Patients in the study were treated with a vaccine targeting cytomegalovirus (CMV) antigen pp65, combined with high-dose chemotherapy (temozolomide) and continuously monitored for toxicity and adverse events. Study patients experienced known side effects with temozolomide, including nausea, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and fatigue.

“This is a small study, but it's one in a sequence of clinical trials we have conducted to explore the use of an immunotherapy that specifically targets a protein on glioblastoma tumors,” explained lead study investigator Kristen Batich, M.D., Ph.D., a research scientist at the Duke Cancer Institute. “While not a controlled efficacy study, the survival results were surprising, and they suggest the possibility that combining the vaccine with a more intense regimen of this chemotherapy promotes a strong cooperative benefit.”

The researchers found that there were no treatment-limiting adverse events and no adverse events related to the cellular portion of the vaccine. One patient developed a grade 3 vaccine-related allergic reaction to the granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) component of the vaccine. The patient was able to continue vaccinations in which the GM-CSF was removed and had no subsequent adverse events.

Though the trial was small and not designed to evaluate the efficacy, 4 of the 11 study patients survived for more than 5 years following treatment with a combination of vaccine and temozolomide, a first-line chemotherapy drug for GBM. That outcome is extremely uncommon for GBM, as the mean survival rate is less than 15 months when treated with the current standard of care.

In the current study, the Duke team utilized a dose-intensified regimen of temozolomide along with a dendritic cell vaccine therapy that selectively targets a CMV protein. CMV proteins are abundant in GBM tumors but are absent in surrounding brain cells. The research team's previous work using the dendritic cell vaccine to teach T cells to attack tumor cells suggested these vaccines could be enhanced when primed by an immune system booster. Moreover, a separate clinical trial found that higher-than-standard doses of temozolomide, combined with an immune-stimulating factor, also primed the immune system and enhanced the response of a different vaccine target.

“Our strategy was to capitalize on the immune deficiency caused by the temozolomide regimen,” Dr. Batich noted. “It seems counterintuitive, but when the patient's lymphocytes are depleted, it's actually an optimal time to introduce the vaccine therapy. It basically gives the immune system marching orders to mount resources to attack the tumor.”

The Duke team found that the innovative approach significantly slowed the progression of patients' tumors. Typically, glioblastoma tumors begin to regrow after standard treatment at a median of 8 months, but recurrence occurred at a median of 25 months for study participants.

“These are surprisingly promising clinical outcomes,” concluded senior study investigator John Sampson, M.D., Ph.D., chair of the department of neurosurgery at Duke University. “However, it is important to emphasize that this was a very small study that used historical comparisons rather than randomizing patients to two different treatments; but the findings certainly support further study of this approach in larger, controlled clinical trials.”