Alex Philippidis Senior News Editor Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News

Legislation and FDA rules have been slow to come, but all voice a sense of urgency.

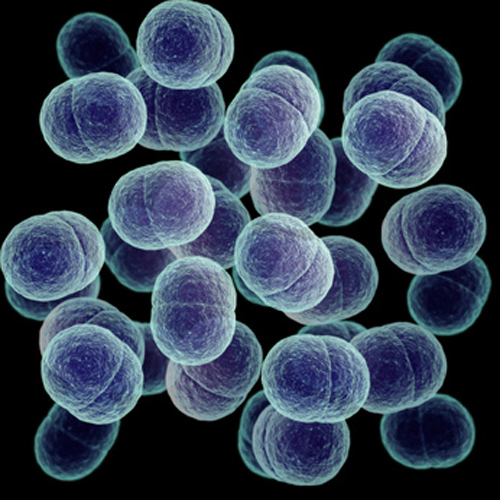

With antibiotic-resistant superbugs seemingly uniting public health groups around developing new antibiotic drugs, FDA signaled last week that it got the message and will respond soon. While FDA offered few details, Commissioner Margaret A. Hamburg, M.D., and Janet Woodcock, M.D., director of FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, offered an outline of how the agency will address the issue.

“We are working to provide scientifically sound guidance to industry on demonstrating the safety and effectiveness of new antibacterial drugs, particularly on indication-specific trial designs used to study a new drug,” Dr. Woodcock testified March 8 before the Health Subcommittee of the House Energy and Commerce Committee.

“Although the development of new antibacterial drugs is not the entire solution to the important public health problem of antimicrobial resistance, it is a very important part,” she added. “We are at a critical juncture in this field. We are in urgent need of new therapeutic options to treat the resistant bacteria that we currently face, and we will need new therapeutic options in the future.”

Dr. Woodcock said FDA is in talks with industry representatives, the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), and others about how drugs should be developed for multidrug-resistant organisms: “A much abbreviated development program, a very small development program, which would be an incentive for developing these types of antibiotics would be highly feasible if it were linked to the concept of good antibiotic stewardship post-market.”

Stephanie Yao, an FDA spokesperson told GEN, “The FDA has been working on a number of efforts to provide industry with updated guidance on recommended clinical trial designs for antibacterial drug development for a variety of conditions. Over the past five years, the agency has issued 10 guidance documents, either as drafts or final, in the area of antibacterial drug development and breakpoints.”

Challenges

Dr. Woodcock pointed out that antibacterial drug development faces several scientific and business challenges: the difficulty of designing clinical trials due to small patient populations; a lack of standardized data; and a decline in funds targeted to developing new drugs.

Additionally, antibiotics are typically priced much lower than most drugs and used for shorter durations than drugs for chronic illnesses, Amanda Jezek, IDSA’s director of government relations, pointed out to GEN. “Chronic drugs are much more profitable for companies than antibiotics, so it’s very challenging to get companies to direct their resources to this space.

“And we also typically want to make sure that antibiotics are not overused,” and thus breed resistance to the drugs, she added. “There are so many challenges to antibiotic development, which underscores the need for some creative thinking about how to get some companies back in the game of developing antibiotics,” Jezek remarked.

One example of the scientific challenge emerged last month. Researchers from Columbia University Medical Center, NIH, and St. George’s University of London detailed how methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) clone ST398-NM has emerged as a significant cause of community-associated infections in humans in the U.S., Europe, and China. Based on samples from 332 Manhattan households, scientists determined ST398-NM efficiently transmits from person to person in part because it adheres well to human skin.

The goal is less curing the disease with drugs than preventing it in healthy people: “Perhaps understanding the risk of a certain strain would help us actually to devise interventions other than drugs,” the study’s lead author Anne-Catrin Uhlemann, M.D., a Columbia researcher, told GEN. “I think it’s more about learning what happens at the molecular epidemiology interface, understanding what these strains mean, and then changing behavior and being preventive.”

Policy and Regulation

IDSA proposes a fast-track FDA approval path including a new Special Population Limited Medical Use (SPLMU) Drugs category for new treatments where few or no therapeutic options exist. The SPLMU designation would allow drugs to be tested in smaller and thus faster clinical trials. FDA appears warm to the idea. Dr. Woodcock noted that the agency could set up general criteria and then make more specific agreements with companies about drug designation when they come in to talk to the FDA about their development programs.

IDSA said that its proposal should be added to a bill pending in Congress, the Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) Act of 2011 (HR 2182). GAIN would extend the exclusivity period for new qualified infectious disease products by five years, on top of any extension for pediatric exclusivity. The extension would not apply to supplemental applications for new indications or modifications to the structure of presently approved drugs. The bill would also give qualified infectious disease products six more months of exclusivity if the sponsor or manufacturer identifies a companion diagnostic test.

IDSA believes GAIN Act is helpful but may not offer enough incentive. The measure should include some exclusivity at the end of existing patent periods plus incentives to defray research R&D such as tax breaks, Jezek said.

Congress should also encourage public-private research collaborations, she added. This is the goal of a program being developed by the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI), a joint effort of EU and European pharmaceutical industry group EFPIA. IMI is preparing a call for proposals to be issued later this year for entities interested in running its “NewDrugs4BadBugs” program, spokeswoman Kim De Rijck told GEN.

Instituting Change More Quickly

The GAIN Act has been in committee since its introduction last June by by Rep. Phil Gingrey, M.D. (R-GA). The companion bill in the Senate (S.1734) was introduced by Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) last October. “Rep. Gingrey anticipates its passage this year,” spokeswoman Jen Talaber told GEN. “He has been working with other members to build consensus for some time and is urging Congress to move forward on this legislation.” The Senate bill has 10 co-sponsors, while Gingrey’s bill has 39.

“The GAIN Act is squarely focused on serious bacterial pathogens, with equally serious unmet medical need, including Gram-negative bacteria,” Rep. Gingrey said. Of particular interest, he said, is Acinetobacter baumannii or “Iraqibacter,” which infected numerous U.S. troops fighting in Iraq.

The GAIN Act would boost federal involvement in supporting antibiotic drug development, overseen for more than a decade by the Interagency Task Force on Antimicrobial Resistance. NIH, CDC, and FDA co-chair the task force, which last year published an updated Public Health Action Plan to Combat Microbial Resistance.

Jezek said IDSA supported many of the updated plan’s ideas but laments that the task force needed four years to publish the update and that no single point person has been named to ensure the task force’s work moves forward. “While there are a lot of really great ideas in there, there aren’t a lot of deadlines and benchmarks for holding the agencies accountable for taking on all of these new ideas and actions.”

NIH/NIAID also belongs to the Trans-Atlantic Task Force on Antimicrobial Resistance (TATFAR). Last year, TATFAR released a report outlining 17 recommendations for future EU-U.S. cooperation, Dennis M. Dixon, chief of the bacteriology and mycology branch of the NIAID, told GEN. TATFAR suggested that policymakers need to consider the establishment of incentives to stimulate antibacterial drug development. It also noted that FDA and EMA should use the same clinical development program and facilitate vaccine development for healthcare-associated infections as well as consultation and collaboration on a survey of point-prevalence for such infections.

The task force’s work highlights the need for continued coordination of antibiotic research and drug development efforts now scattered among several agencies. But coordination should not be a reason to slow down the urgent work of developing drugs and vaccines. Given the consensus in Congress, some form of GAIN Act will likely pass, either as a standalone bill or an amendment to the proposed fifth authorization of the Prescription Drug User Fees Act pending before Congress. The GAIN Act poses an opportunity to evaluate various initiatives, with an eye to bringing under a single umbrella all federally funded efforts to understand both how the pathogens function and how to eradicate them with drugs and preventive efforts.

Alex Philippidis is senior news editor at Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News.