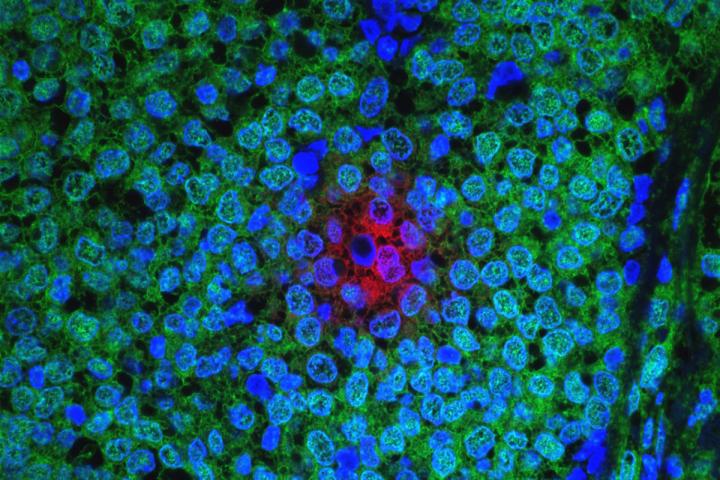

![In this image of a human breast tumor, a cluster of malignant cells that have become resistant to chemotherapy are shown in red. [NCI]](https://genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Jun7_2017_NCI_HumanBreastTumor2553817212-1.jpg)

In this image of a human breast tumor, a cluster of malignant cells that have become resistant to chemotherapy are shown in red. [NCI]

Scientists at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine say that cancer cells seem to communicate to other cancer cells, activating an internal system that increases resistance to chemotherapy and promotes tumor survival. Their study (“Intercellular Transmission of the Unfolded Protein Response Promotes Survival and Drug Resistance in Cancer Cells”) appears online in Science Signaling.

Six years ago, Maurizio Zanetti, M.D., professor in the department of medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine and a tumor immunologist at Moores Cancer Center at UC San Diego Health, published a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggesting that cancer cells exploit an internal mechanism used by stressed mammalian cells, called the unfolded protein response (UPR), to communicate with immune cells, notably cells derived from the bone marrow, giving them protumorigenic characteristics. The UPR is activated in response to unfolded or misfolded proteins accumulating in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and can often decide apoptosis or survival.

In their new paper, Dr. Zanetti's team reports that cancer cells appear to take the process beyond just affecting bone marrow cells, using transmissible ER stress (TERS) to activate Wnt signaling in recipient cancer cells.

“We noticed that TERS-experienced cells survived better than their unexperienced counterparts when nutrient-starved or treated with common chemotherapies like bortezomib or paclitaxel,” said Jeffrey J. Rodvold, Ph.D., a member of Zanetti's lab and first author of the study. “In each instance, receiving stress signals caused cells to survive better. Understanding how cellular fitness is gained within the tumor microenvironment is key to understanding cooperativity among cancer cells as a way to collective resilience to nutrient starvation and therapies.”

When cancer cells subject to TERS were implanted in mice, they produced faster growing tumors.

“Our data demonstrates that transmissible ER stress is a mechanism of intercellular communication,” said Dr. Zanetti. “We know that tumor cells live in difficult environments, exposed to nutrient deprivation and lack of oxygen, which in principle should restrict tumor growth. Through stress transmission, tumor cells help neighboring tumor cells to cope with these adverse conditions and eventually survive and acquire growth advantages.”

He added that the research may explain previous findings by other groups showing that individual tumor cells within a uniform genetic lineage can acquire functionally different behaviors in vivo, i.e., some cells acquire greater fitness and extended survival. This represents another way to generate intratumor heterogeneity, the basis of one of the key roadblocks to cancer treatment. This implies that mutations throughout the cancer genome of an individual are not the only source of intratumor heterogeneity.

According to Dr. Zanetti, researchers and doctors need to consider these changing cellular dynamics in the tumor microenvironment in developing both a better understanding of cancer and more effective treatments.