Karen Weintraub Contributor GEN

Elusive so Far, but Crucial for Drug Development and Research

It’s long been a conundrum for Alzheimer’s researchers: without an inexpensive way to diagnose the disease, it’s been hard to study and develop drugs to treat it, but there won’t be a market for a diagnostic test until someone develops a drug that can improve patients’ lives.

About five years ago, researchers realized that PET scans of the brain could reveal a build-up of beta-amyloid, the clumps of protein that are the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease. But such scans can cost thousands of dollars and are difficult to administer.

Now, scientists in Japan have shown in early research that they can accurately predict the deposition of amyloid 90% of the time using a simple blood test.

Writing in the journal Nature, the team reported that they could identify individuals with amyloid deposition among cognitively normal people, people with mild cognitive impairment, and patients with Alzheimer’s disease, in a group from Japan and another from Australia.

The study groups were small—121 samples from Japan and 252 from Australia—so the test’s effectiveness will need to be verified in much larger samples.

But the new diagnostic is promising, experts not involved in the work said.

“While this is still early and it certainly needs further evaluation and validation in a larger and more diverse population, it certainly is a step in that right direction,” said Heather Snyder, Ph.D., senior director of medical and scientific operations for the Alzheimer’s Association, an advocacy, support, and research organization.

The test works by detecting differential levels of beta-amyloid. The team analyzed the samples using mass spectrometry, in a system developed in part by one of the study’s coauthors, Koichi Tanaka, who won a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2002 for his work.

The paper’s senior author, Katsuhiko Yanagisawa, M.D., the director-general of the Research Institute at the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology in Aichi, Japan, said it was this technology that allowed his team to accomplish what others were unable to.

“Many groups previously tried to quantitate the amount of Aßs [beta-amyloids] in the plasma and asked whether it correlated with the pathological degree of amyloid deposition in the brain,” he wrote in an email. “However, determination of levels of Aßs in plasma is very difficult due to several reasons. Thus, the results of those studies were not satisfactory to predict the level of Aß deposition.”

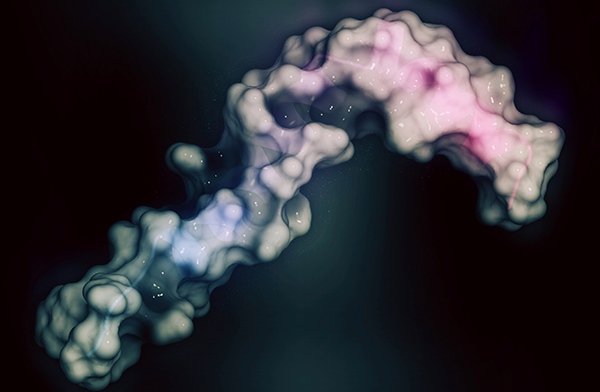

Dr. Yanagisawa and his colleagues were able to separate the protein antigens out of the blood, and then used mass spectrometry to obtain the ratios of amyloid-β precursor protein (APP)669–711 to amyloid-β (Aβ)1–42 and Aβ1–40/Aβ1–42. The researchers found these ratios to be predictive of brain amyloid buildup.

Advances like this one suggest that an inexpensive diagnostic is now an obtainable goal, said Reisa Sperling, M.D., who is a professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and also works at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“I don’t know that this one is it,” she said in an interview, “but I am convinced that over the next few years, we’ll have a blood test that substantially improves our ability to detect amyloid before people have symptoms. So I’m excited about that.”

Dr. Sperling said it’s been challenging to develop a blood-based diagnostic, in part because early studies—performed in the absence of a gold standard for identifying people with the disease—had muddied study populations.

Back then, researchers took blood samples from cognitively normal older people and compared them with samples from people with dementia to look for distinguishing markers. But 30% of older adults who are cognitively normal already have amyloid in their brains, and 20–25% of dementia patients have a condition other than Alzheimer’s, so they don’t have amyloid buildup. “So, you can imagine that that overlap is a mess,” she said.

Many of those early blood tests might have accurately detected the difference between Alzheimer’s patients and those without the disease, Dr. Sperling said, but there was no way to tell. “Maybe we had the blood test all along and didn’t have the right gold standard.”

Now, with PET scans as a definitive standard, tests like the new one can be compared with results from PET scans, and study participants can be accurately separated into those with Alzheimer’s and those without, she said.

But PETs are expensive. Dr. Sperling said she spent most of the budget for the A4 drug trial she’s running now on PET scans. Hers are relatively inexpensive at about $2,500 each, she said; a patient who wanted one might have to pay as much as $5,000, and not all insurance companies will cover the cost, because there are no better treatments to offer people whose disease is confirmed.

Although a blood test is expected to be substantially cheaper than PET, the demand will still lag until there is a treatment available to benefit diagnosed patients, Dr. Yanagisawa said.

“For the public use of any biomarkers for AD, including ours, we need to develop disease-modifying drugs which are proved in terms of their efficacy and safety,” he said. “We hope our method accelerate clinical trials of those candidates.”

Amyloid buildup in the brain might actually be heterogeneous, with some clumps proving to be harmless, and others associated with disease, Dr. Yanagisawa noted. He hopes to study whether his test can characterize the heterogeneity of amyloid, and also help detect amyloid buildup at the earliest stages of disease.

“We strongly hope our method contributes to understanding AD and also facilitates clinical trials of AD, in which early detection of amyloid deposition is crucially required,” Dr. Yanagisawa said in his email.