Although the medical community insists that it needs ways to detect Alzheimer’s disease earlier, it still struggles with diagnostic techniques that are not only invasive, but expensive as well. Even worse, these techniques—which involve lumbar punctures or PET scans—are not readily available at many locations. Without early detection methods that are both easily applied and readily available, researchers will continue to have difficulty moving treatment and prevention trials earlier in the course of the disease. In addition, patients will be slow to take advantage of whatever preventative measures become available.

The barriers to early detection, however, may soon become less daunting now that researchers have found new ways to assess people for Alzheimer’s disease. At the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2014 in Copenhagen, four studies were presented that point to new detection techniques. These techniques promise not only convenience, but also early detection of Alzheimer’s.

In two of the studies, the decreased ability to identify odors was significantly associated with loss of brain cell function and progression to Alzheimer’s disease. In two other studies, the level of beta-amyloid detected in the eye (a) was significantly correlated with the burden of beta-amyloid in the brain and (b) allowed researchers to accurately identify the people with Alzheimer’s in the studies.

The studies were as follows:

- Olfactory identification and Alzheimer's disease biomarkers in clinically normal elderly (presented by researchers representing Harvard Medical School). In a study population of 215 clinically normal elderly individuals, a smaller hippocampus and a thinner entorhinal cortex were associated with worse smell identification and worse memory. The scientists also found that, in a subgroup of study participants with elevated levels of amyloid in their brain, greater brain cell death, as indicated by a thinner entorhinal cortex, was significantly associated with worse olfactory function—after adjusting for variables including age, gender, and an estimate of cognitive reserve.

- Olfactory identification deficits predict the transition from MCI to AD in a multi-ethnic community sample (presented by researchers representing Columbia University). In 757 subjects who were followed in this study, lower odor identification scores on UPSIT were significantly associated with the transition to dementia and Alzheimer's disease, after controlling for demographic, cognitive, and functional measures, language of administration, and apolipoprotein E genotype. For each point lower that a person scored on the UPSIT, the risk of Alzheimer's increased by about 10%. Further, lower baseline UPSIT scores, but not measures of verbal memory, were significantly associated with cognitive decline in participants without baseline cognitive impairment.

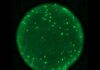

- Retinal amyloid fluorescence imaging predicts cerebral amyloid burden and Alzheimer's disease (presented by researchers representing the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, or CSIRO). This group reported preliminary results of a study of volunteers who took a proprietary supplement containing curcumin, which binds to beta-amyloid with high affinity and has fluorescent properties that allow amyloid plaques to be detected in the eye using a novel system from NeuroVision Imaging, and a technique called retinal amyloid imaging (RAI). Volunteers also underwent brain amyloid PET imaging to correlate the retina and brain amyloid accumulation. An abstract prepared by the scientists for AAIC 2014 gives the results for 40 participants out of 200 total in the study. Preliminary results suggest that amyloid levels detected in the retina were significantly correlated with brain amyloid levels as shown by PET imaging. The retinal amyloid test also differentiated between Alzheimer's and non-Alzheimer's subjects with 100% sensitivity and 80.6% specificity.

- Detection of ligand bound to beta amyloid in the lenses of human eyes (presented by researchers representing Cognoptix). This group reported the results of a study of a fluorescent ligand eye scanning (FLES) system that detects beta-amyloid in the lens of the eye using a topically applied ointment that binds to amyloid and a laser scanner. The researchers studied 20 people with probable Alzheimer’s disease, including mild cases, and 20 age-matched healthy volunteers. The ointment was applied to the inside of participants’ lower eyelids the day before measurement. Laser scanning detected beta-amyloid in the eye by the presence of a specific fluorescent signature; brain amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) scanning was performed on all participants to estimate amyloid plaque density in the brain. Using results from the fluorescent imaging, researchers were able to differentiate people with Alzheimer’s from healthy controls with high sensitivity (85%) and specificity (95%). In addition, amyloid levels based on the eye lens test correlated significantly with results obtained through PET brain imaging.

“In the face of the growing worldwide Alzheimer’s disease epidemic, there is a pressing need for simple, less invasive diagnostic tests that will identify the risk of Alzheimer's much earlier in the disease process,” said Heather Snyder, Ph.D., Alzheimer’s Association director of Medical and Scientific Operations. “This is especially true as Alzheimer’s researchers move treatment and prevention trials earlier in the course of the disease.”

“More research is needed in the very promising area of Alzheimer’s biomarkers because early detection is essential for early intervention and prevention, when new treatments become available,” Dr. Snyder added. “For now, these four studies reported at AAIC point to possible methods of early detection in a research setting to choose study populations for clinical trials of Alzheimer's treatments and preventions.”