Although we are accustomed to computer viruses, we remain confident that the kind of infectious code that threatens biological systems remains distinct from the kind of code that threatens computer systems. We may need to lose the false sense of security. Code that can bridge the biological/computational divide is an unnerving possibility, one demonstrated by a team of computer scientists based at University of Washington.

The team has demonstrated for the first time that it is possible—though still challenging—to compromise a computer system with a malicious computer code stored in synthetic DNA. When that DNA is analyzed, the code can become executable malware that attacks the computer system running the software.

The team also analyzed the security hygiene of common, open-source DNA-processing programs to uncover evidence of poor computer security practices used throughout the field.

These findings emerged from a study that will be presented August 17 in Vancouver, B.C., at the 26th USENIX Security Symposium. The study, entitled “Computer Security, Privacy, and DNA Sequencing: Compromising Computers with Synthesized DNA, Privacy Leaks, and More,” is already available at the team’s website.

“We demonstrate … the synthesis of DNA which—when sequenced and processed—gives an attacker arbitrary remote code execution,” the article’s authors wrote. “To study the feasibility of creating and synthesizing a DNA-based exploit, we performed our attack on a modified downstream sequencing utility with a deliberately introduced vulnerability. After sequencing, we observed information leakage in our data due to sample bleeding. While this phenomenon is known to the sequencing community, we provide the first discussion of how this leakage channel could be used adversarially to inject data or reveal sensitive information.”

So far, the researchers stress, there's no evidence of malicious attacks on DNA synthesizing, sequencing, and processing services. But their analysis of software used throughout that pipeline found known security gaps that could allow unauthorized parties to gain control of computer systems—potentially giving them access to personal information or even the ability to manipulate DNA results.

“One of the big things we try to do in the computer security community is to avoid a situation where we say, 'Oh shoot, adversaries are here and knocking on our door and we're not prepared,'” said co-author Tadayoshi Kohno, Ph.D., professor at the UW's Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering.

“Instead, we'd rather say, 'Hey, if you continue on your current trajectory, adversaries might show up in 10 years. So, let's start a conversation now about how to improve your security before it becomes an issue,'” said Kohno, whose previous research has provoked high-profile discussions about vulnerabilities in emerging technologies, such as internet-connected automobiles and implantable medical devices.

“We don't want to alarm people or make patients worry about genetic testing, which can yield incredibly valuable information,” said co-author and Allen School associate professor Luis Ceze, Ph.D. “We do want to give people a heads up that as these molecular and electronic worlds get closer together, there are potential interactions that we haven't really had to contemplate before.”

In the new paper, researchers from the UW Security and Privacy Research Lab and UW Molecular Information Systems Lab (MISL) offer recommendations to strengthen computer security and privacy protections in DNA synthesis, sequencing, and processing.

The research team identified several different ways that a nefarious person could compromise a DNA sequencing and processing stream. To start, they demonstrated a technique that is scientifically fascinating—though arguably not the first thing an adversary might attempt, the researchers say.

“It remains to be seen how useful this would be, but we wondered whether under semirealistic circumstances it would be possible to use biological molecules to infect a computer through normal DNA processing,” said co-author and Allen School doctoral student Peter Ney.

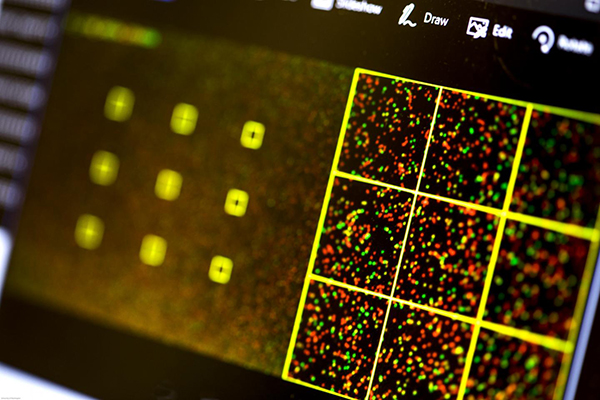

DNA is, at its heart, a system that encodes information in sequences of nucleotides. Through trial and error, the team found a way to include executable code—similar to computer worms that occasionally wreak havoc on the internet—in synthetic DNA strands.

To create optimal conditions for an adversary, they introduced a known security vulnerability into a software program that's used to analyze and search for patterns in the raw files that emerge from DNA sequencing.

When that particular DNA strand is processed, the malicious exploit can gain control of the computer that's running the program—potentially allowing the adversary to look at personal information, alter test results, or even peer into a company's intellectual property.

“To be clear, there are lots of challenges involved,” said co-author Lee Organick, a research scientist in the Molecular Information Systems Lab. “Even if someone wanted to do this maliciously, it might not work. But we found it is possible.”

In what might prove to be a more target-rich area for an adversary to exploit, the research team also discovered known security gaps in many open-source software programs used to analyze DNA sequencing data.

Some were written in unsafe languages known to be vulnerable to attacks, in part because they were first crafted by small research groups who likely weren't expecting much, if any, adversarial pressure. But as the cost of DNA sequencing has plummeted over the last decade, open-source programs have been adopted more widely in medical- and consumer-focused applications.

Researchers at the UW MISL are working to create next-generation archival storage systems by encoding digital data in strands of synthetic DNA. Although their system relies on DNA sequencing, it does not suffer from the security vulnerabilities identified in the present research, in part because the MISL team has anticipated those issues and because their system doesn't rely on typical bioinformatics tools.

Recommendations to address vulnerabilities elsewhere in the DNA sequencing pipeline include: following best practices for secure software, incorporating adversarial thinking when setting up processes, monitoring who has control of the physical DNA samples, verifying sources of DNA samples before they are processed, and developing ways to detect malicious executable code in DNA.

“There is some really low-hanging fruit out there that people could address just by running standard software analysis tools that will point out security problems and recommend fixes,” said co-author Karl Koscher, Ph.D., a research scientist in the UW Security and Privacy Lab. “There are certain functions that are known to be risky to use, and there are ways to rewrite your programs to avoid using them. That would be a good initial step.”