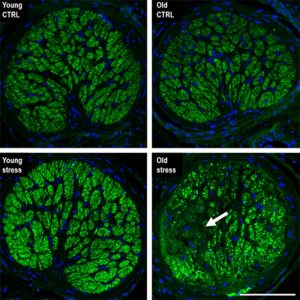

There is a wide range of eye diseases that can compromise vision, and many of them have been linked to aging. A new study in mice by researchers from the University of California, Irvine (UCI) demonstrates that stress, such as intraocular pressure (IOP) elevation in the eye, causes retinal tissue to undergo epigenetic changes similar to natural aging. Their findings reveal repetitive stress induces features of accelerated aging.

The study is published in Aging Cell in an article titled, “Stress induced aging in mouse eye,” and led by Dorota Skowronska‐Krawczyk, PhD, assistant professor in the departments of physiology & biophysics and ophthalmology and the faculty of the Center for Translational Vision Research at the UCI School of Medicine.

“Aging, a universal process that affects all cells in an organism, is a major risk factor for a group of neuropathies called glaucoma, where elevated intraocular pressure is one of the known stresses affecting the tissue,” wrote the researchers. “Our understanding of the molecular impact of aging on response to stress in the retina is very limited; therefore, we developed a new mouse model to approach this question experimentally. Here we show that susceptibility to response to stress increases with age and is primed on the chromatin level. We demonstrate that ocular hypertension activates a stress response that is similar to natural aging and involves activation of inflammation and senescence.”

In humans, IOP has a circadian rhythm. Long-term IOP fluctuation has been reported to be a strong predictor for glaucoma progression. The new study by UCI researchers suggests that the cumulative impact of the fluctuations of IOP is directly responsible for the aging of the tissue.

“Our work shows that even moderate hydrostatic IOP elevation results in retinal ganglion cell loss and corresponding visual defects when performed on aged animals,” said Skowronska-Krawczyk. “We are continuing to work to understand the mechanism of accumulative changes in aging in order to find potential targets for therapeutics. We are also testing different approaches to prevent the accelerated aging process resulting from stress.”

“In addition to measuring vision decline and some structural changes due to stress and potential treatment, we can now measure the epigenetic age of retinal tissue and use it to find the optimal strategy to prevent vision loss in aging,” said Skowronska-Krawczyk.

The findings may pave the way for designing new treatments for glaucoma patients.