Scientists led by Cunjiang Yu, PhD, Bill D. Cook Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Houston, have developed a new form of electronics known as “drawn-on-skin electronics,” allowing multifunctional sensors and circuits to be drawn on the skin with an ink pen.

The advance, described in a paper entitled “Ultra-conformal drawn-on-skin electronics for multifunctional motion artifact-free sensing and point-of-care treatment,” in Nature Communications, allows for the collection of more precise, motion artifact-free health data, solving the long-standing problem of collecting precise biological data through a wearable device when the subject is in motion, according to the researchers.

“An accurate extraction of physiological and physical signals from human skin is crucial for health monitoring, disease prevention, and treatment. Recent advances in wearable bioelectronics directly embedded to the epidermal surface are a promising solution for future epidermal sensing. However, the existing wearable bioelectronics are susceptible to motion artifacts as they lack proper adhesion and conformal interfacing with the skin during motion,” write the investigators.

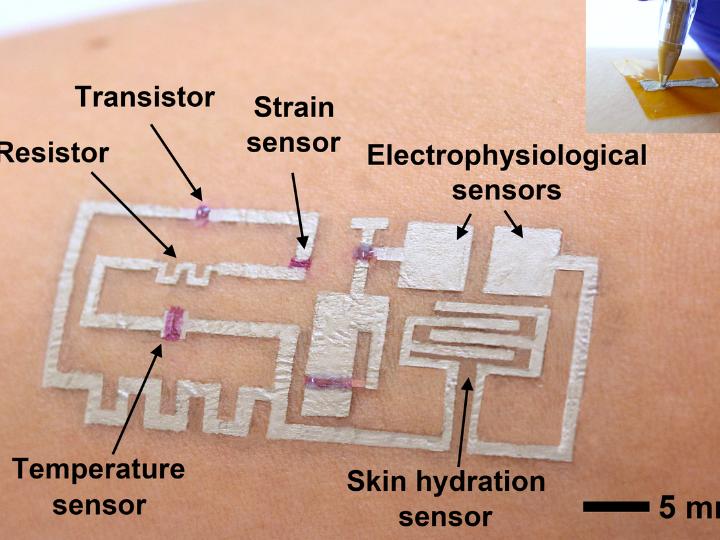

“Here, we present ultra-conformal, customizable, and deformable drawn-on-skin electronics, which is robust to motion due to strong adhesion and ultra-conformality of the electronic inks drawn directly on skin. Electronic inks, including conductors, semiconductors, and dielectrics, are drawn on-demand in a freeform manner to develop devices, such as transistors, strain sensors, temperature sensors, heaters, skin hydration sensors, and electrophysiological sensors.”

“Electrophysiological signal monitoring during motion shows drawn-on-skin electronics’ immunity to motion artifacts. Additionally, electrical stimulation based on drawn-on-skin electronics demonstrates accelerated healing of skin wounds.”

The imprecision may not be important when your FitBit registers 4,000 steps instead of 4,200, but sensors designed to check heart function, temperature and other physical signals must be accurate if they are to be used for diagnostics and treatment.

The drawn-on-skin electronics are able to collect data, regardless of the wearer’s movements. They also offer other advantages, including simple fabrication techniques that don’t require dedicated equipment.

“It is applied like you would use a pen to write on a piece of paper,” said Yu. “We prepare several electronic materials and then use pens to dispense them. Coming out, it is liquid. But like ink on paper, it dries very quickly.”

Wearable bioelectronics, in the form of soft, flexible patches attached to the skin, have become an important way to monitor, prevent and treat illness and injury by tracking physiological information from the wearer. But even the most flexible wearables are limited by motion artifacts, or the difficulty that arises in collecting data when the sensor doesn’t move precisely with the skin.

The drawn-on-skin electronics can be customized to collect different types of information, and Yu said it is expected to be especially useful in situations where it’s not possible to access sophisticated equipment, including on a battleground.

The electronics are able to track muscle signals, heart rate, temperature and skin hydration, among other physical data, he said. The researchers also reported that the drawn-on-skin electronics have demonstrated the ability to accelerate healing of wounds.

The drawn-on-skin electronics are actually comprised of three inks, serving as a conductor, semiconductor, and dielectric.

“Electronic inks, including conductors, semiconductors, and dielectrics, are drawn on-demand in a freeform manner to develop devices, such as transistors, strain sensors, temperature sensors, heaters, skin hydration sensors, and electrophysiological sensors,” the team pointed out.