An international study in zebrafish led by the medical faculty of the University of Bonn has discovered the gene, SHROOM4, plays an important role in the development of the human embryo. Their findings demonstrate that if the gene is altered, malformations of various organ systems can result.

The results have now been published in the Journal of Medical Genetics in an article titled, “X-linked variations in SHROOM4 are implicated in congenital anomalies of the urinary tract, the anorectal, the cardiovascular, and the central nervous system.”

“SHROOM4 is thought to play an important role in cytoskeletal modification and development of the early nervous system,” wrote the researchers. “Previously, single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) or copy number variations (CNVs) in SHROOM4 have been associated with the neurodevelopmental disorder Stocco dos Santos syndrome, but not with congenital anomalies of the urinary tract and the visceral or the cardiovascular system.”

The researchers uncovered the gene when they studied two individuals with congenital malformations. “It was a man and his niece,” explained Gabriel Dworschak, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Bonn. “Both had malformed kidneys, urinary tract, and esophagus, and the man also had a malformed right arm and heart.”

When the team looked at the genetic makeup of the family members, they came across an anomaly: A gene called SHROOM4 was altered in affected individuals compared to healthy individuals.

SHROOM4 was already known to play a key role in brain function. Mutations can result in intellectual impairment, epileptic seizures, and behavioral abnormalities. “Our findings indicated though, that it may play a broader role in embryonic organ development,” Dworschak explained.

The team from Bonn searched internationally for other cases in which abnormalities in the SHROOM4 gene had also been found. “Together with our cooperation partners, this led us to four more affected individuals from three families,” said professor Heiko Reutter, PhD, who has since moved from the University Hospital Bonn to the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg. “All of them had the SHROOM4 gene altered, but not always in the same way.”

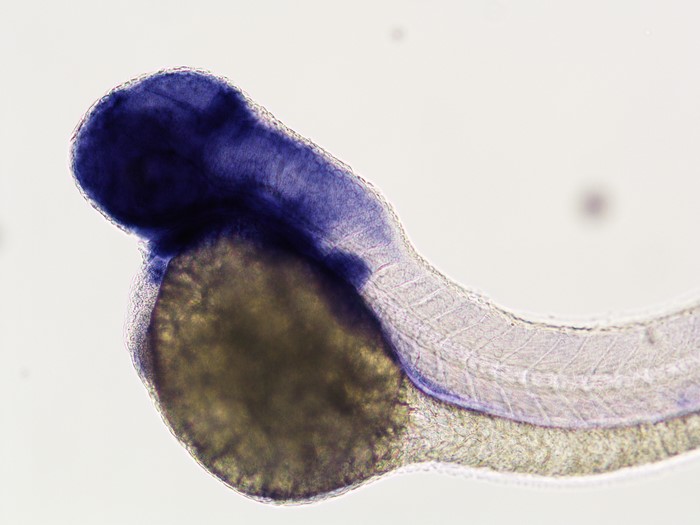

Using exome sequencing and copy number variation analyses in zebrafish to study the role of SHROOM4 during embryonic development.

“Here at the University Hospital, we have the advantage that the research group led by Prof. Benjamin Odermatt, PhD, from the Institute of Neuroanatomy works a lot with zebrafish,” stressed Caroline Kolvenbach, PhD, who was also involved in the study of SHROOM4. “This expertise came in handy in our study.”

The researchers almost completely inactivated SHROOM4 in the larvae. The animals then showed malformations similar to those seen in the patients. If, on the other hand, larvae with SHROOM4 switched off were injected with the intact human genetic material, they developed almost normally. “This shows first that they absolutely need a functional SHROOM4 for healthy development; and second, that the human gene can still take over the function of the fish gene,” Dworschak emphasized.

The researchers are now trying to uncover which part the gene plays in embryonic development. “We assume that it is needed for very basic processes in the cell,” explained Dworschak. “It’s hard to explain otherwise why changes in the same gene cause such a variety of symptoms. Our study is a small piece of the mosaic to this picture, which is still largely incomplete,” Dworschak concluded.