If you gaze long into the dish, the dish also gazes into you. In this case, the dish contains cultured retinal cells, which can allow us to see into the genetic depths of acute macular degeneration (AMD), revealing variants that we may fear and loathe, but with which we must, nonetheless, come to terms.

Using eye-in-a-dish models, researchers based at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), revealed the importance of a specific genetic variation that affects expression of the VEGFA gene. The product of this gene, the VEGFA protein, is known for supporting new blood vessel growth—a process that goes awry in AMD.

When the gene variant is present, the amount of VEGFA protein is reduced, directly contributing to AMD, one of the most common causes of vision loss in people over age 65.

Although AMD’s exact cause is unclear, it has been established that a family history of AMD increases a person’s risk for the condition. To further substantiate this hereditary and presumably genetic connection, the UCSD researchers decided to search for causal variants. They chose to look deeply into retinal pigment epithelium that had been recapitulated in the lab.

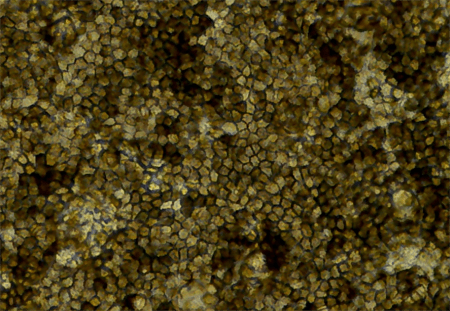

This eye-in-a-dish model was generated from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Researchers first obtained skin samples from six people, then converted skin cells into iPSCs as an intermediary. Like all stem cells, iPSCs can both self-renew, making more iPSCs, and differentiate into a specialized cell type. With the right cocktail of molecules and growth factors, the researchers specifically coaxed iPSCs into becoming retinal cells. The resulting eye-in-a-dish model took on physiological and molecular characteristics similar to native retinal cells, including a polygonal shape and pigmentation.

Details of this work appeared May 9 in the journal Stem Cell Reports, in an article titled, “Human iPSC-Derived Retinal Pigment Epithelium: A Model System for Prioritizing and Functionally Characterizing Causal Variants at AMD Risk Loci.” This article describes a potential mechanism underlying the association of the VEGFA locus with AMD.

“We didn’t start with the VEGFA gene when we went looking for genetic causes of AMD,” said senior author Kelly A. Frazer, PhD, professor of pediatrics and director of the Institute for Genomic Medicine at UCSD School of Medicine. “But we were surprised to find that, with samples from just six people, this genetic variation clearly emerged as a causal factor.”

Frazer and colleagues collected molecular data, including RNA transcripts and epigenetic information, from the retinal models. They integrated this new data with complementary published data from 18 adults with and without AMD.

“We generated RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and H3K27ac ChIP-seq data and observed high similarity in gene expression and enriched transcription factor motif profiles between iPSC-RPE and human fetal RPE,” the article’s authors indicated. “We performed fine mapping of AMD risk loci by integrating molecular data from the iPSC-RPE, adult retina, and adult RPE, which identified rs943080 as the probable causal variant at VEGFA. We show that rs943080 is associated with altered chromatin accessibility of a distal ATAC-seq peak, decreased overall gene expression of VEGFA, and allele-specific expression of a noncoding transcript.”

AMD involves the slow breakdown of cells that make up the macula, which is part of the retina, a region in the back of the eye that sends information to the brain. The most common treatment for AMD is injections of a drug that inhibits VEGF. This therapy blocks the formation of new blood vessels and leakage from abnormal vessels.

“Since current AMD therapies work by inhibiting VEGF, we knew VEGF was involved in AMD,” noted Agnieszka D’Antonio-Chronowska, PhD, a researcher in Frazer’s lab and one of the study’s co-authors. “But we were surprised that the causal variant results in decreased VEGFA expression prior to AMD onset, and this finding could potentially be relevant for the treatment of AMD using anti-VEGF therapeutics.”