Researchers at the Scripps Research Institute say their genetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus and related viruses has found no evidence that SARS-CoV-2 is the result of bioengineering in a lab. Rather, said Kristian Andersen, PhD, an associate professor of immunology and microbiology at Scripps Research and corresponding author of the published report in Nature Medicine, “By comparing the available genome sequence data for known coronavirus strains, we can firmly determine that SARS-CoV-2 originated through natural processes.” And as Andersen and colleagues concluded, the results “clearly show that SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus.”

Andersen is corresponding author of the team’s paper, which is titled, “The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2.” Co-authors include Robert F. Garry, PhD, professor at Tulane University; Edward Holmes, PhD, professor at the University of Sydney; Andrew Rambaut, PhD, professor at the University of Edinburgh; and W. Ian Lipkin, PhD, professor at Columbia University.

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses that can cause illnesses ranging widely in severity. The first known severe illness caused by a coronavirus emerged with the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic in China. A second outbreak of severe illness began in 2012 in Saudi Arabia with the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). In fact, “SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh coronavirus known to infect humans,” the authors wrote. But unlike MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV, which can cause severe disease, “… HKU1, NL63, OC43, and 229E are associated with mild symptoms.”

On December 31 of last year, Chinese authorities alerted the World Health Organization of an outbreak of a novel strain of coronavirus causing severe illness, which was subsequently named SARS-CoV-2. As of March 17, there were 179,111 confirmed cases, and 7,426 coronavirus-related deaths, according to WHO figures.

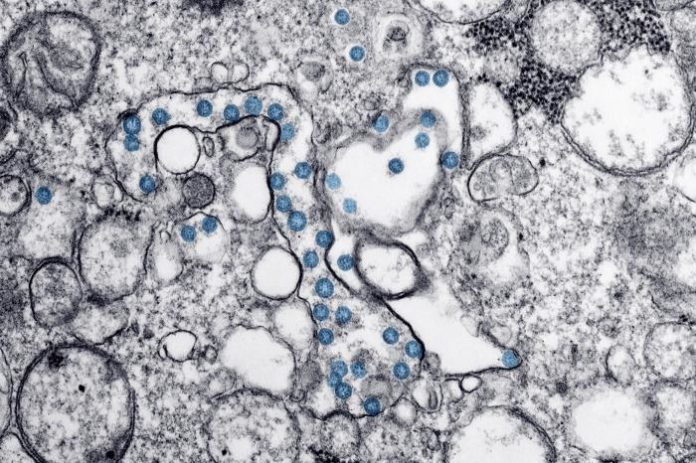

Shortly after the epidemic began, Chinese scientists sequenced the genome of SARS-CoV-2 and made the data available to researchers worldwide. The resulting genomic sequence data have shown that Chinese authorities rapidly detected the epidemic and that the number of COVID-19 cases has been increasing because of human-to-human transmission after a single introduction into the human population.

Andersen and collaborators have used this sequencing data to explore the origins and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 by focusing in on tell-tale features of the virus. “We review what can be deduced about the origin of SARS-CoV-2 from comparative analysis of genomic data,” they wrote. “We offer a perspective on the notable features of the SARS-CoV-2 genome and discuss scenarios by which they could have arisen.”

For their studies, the scientists analyzed the genetic template for the viral spike proteins on the outside of SARS-CoV-2 that the virus uses to bind to cell surface receptors and gain entry into human host cells. They focused on two important features of the spike protein: the receptor-binding domain (RBD), and the spike’s polybasic furin cleavage site, which is involved in gaining entry through the host cell’s outer membrane—effectively a molecular can opener.

The evidence for natural evolution of the virus was supported by data on the SARS-CoV-2 backbone—its overall molecular structure. If someone was seeking to engineer a new coronavirus as a pathogen, they would have constructed it from the backbone of a virus known to cause illness. But the scientists found that the SARS-CoV-2 backbone differed substantially from those of already known coronaviruses and mostly resembled related viruses found in bats and pangolins. “… the genetic data irrefutably show that SARS-CoV-2 is not derived from any previously used virus backbone,” the scientists stated in their report. Andersen added, “These two features of the virus, the mutations in the RBD portion of the spike protein and its distinct backbone, rule out laboratory manipulation as a potential origin for SARS-CoV-2.”

Based on their genomic sequencing analysis, Andersen and his collaborators concluded that evolution of SARS-CoV-2 followed one of two possible scenarios from its origins. In one scenario, the virus evolved into its current pathogenic state through natural selection in a non-human host, and then jumped to humans. This is how previous coronavirus outbreaks have emerged, with humans contracting the virus after direct exposure to civets, in the case of SARS, and to camels, in the case of MERS. The researchers have proposed bats as the most likely reservoir for SARS-CoV-2 as this virus is very similar to a bat coronavirus. There are no documented cases of direct bat-human transmission, however, suggesting that an intermediate host was likely involved somewhere between bats and humans.

In this first scenario, both of the distinctive features of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein—the RBD portion that binds to cells and the cleavage site involved in getting the virus into the host cell—would have evolved to their current states prior to the virus jumping to humans. SARS-CoV-2 spread would probably then have been rapid, as soon as humans were infected, because the virus would have already evolved the key features that make it pathogenic and able to pass between people.”

In the other proposed scenario, a non-pathogenic version of the virus jumped from an animal host into humans and then evolved to its current pathogenic state within the human population. For instance, some coronaviruses from pangolins have an RBD structure that is very similar to that of SARS-CoV-2. A coronavirus from a pangolin could possibly have been transmitted to a human, either directly or through an intermediary host, such as civets or ferrets. In this scenario, the other distinct spike protein characteristic of SARS-CoV-2, the cleavage site, could have evolved within a human host, possibly via limited undetected circulation in the human population prior to the beginning of the epidemic.

“The presence in pangolins of an RBD very similar to that of SARS-CoV-2 means that we can infer this was also probably in the virus that jumped to humans,” the authors noted. “This leaves the insertion of polybasic cleavage site to occur during human-to-human transmission.” In effect, there would be a period of “unrecognized transmission” in humans, between the initial jump from animal to human, or the zoonotic event, and the acquisition of the polybasic cleavage site.

The researchers also found that the SARS-CoV-2 cleavage site appears similar to the cleavage sites of strains of bird flu that have been shown to transmit easily between people. It’s feasible that SARS-CoV-2 could have evolved such a virulent cleavage site in human cells, at which point the coronavirus would possibly have become far more capable of spreading between people, and so started the epidemic.

Study co-author Rambaut cautioned that it is difficult, if not impossible, to know at this stage which of the scenarios is the one that has actually played out. “More scientific data could swing the balance of evidence to favor one hypothesis or another,” the researchers acknowledged.

If the SARS-CoV-2 entered humans in its current pathogenic form from an animal source, it raises the probability of future outbreaks, as the pathogenic strain of the virus could still be circulating in the animal population and might once again jump into humans. The chances are lower of a non-pathogenic coronavirus entering the human population and then evolving properties similar to SARS-CoV-2. Whichever of the two scenarios is most likely, the researchers reiterated, that “… since we observed all notable SARS-CoV-2 features, including the optimized RBD and polybasic cleavage site, in relation to coronaviruses in nature, we do not believe that any type of laboratory-based scenario is plausible.”

Josie Golding, PhD, epidemics lead at U.K.-based Wellcome Trust, who isn’t one of the paper’s authors, said the findings by Andersen and colleagues are “crucially important to bring an evidence-based view to the rumors that have been circulating about the origins of the virus (SARS-CoV-2) causing COVID-19”. Goulding noted, “They conclude that the virus is the product of natural evolution, ending any speculation about deliberate genetic engineering.”

Comments are closed.