The battle to maintain genomic integrity is constantly being fought within every cell of the body. Molecules that seek to disrupt the proper flow of genetic information come from both exogenous and endogenous sources. Thankfully, our cells come stacked with an array of defenses that help preserve genomic fidelity, keeping cells from succumbing to deleterious alterations or wandering down the path toward carcinogenesis. A full understanding of these DNA damage repair mechanisms is vital to thwarting cancer and preventing its spread.

Now, investigators at Tufts University School of Medicine believe they may have just found evidence that a transcription factor called Slug serves as “command central” for determining breast stem cell health, regulating both stem cell activity and repair of DNA damage. Moreover, the research team also discovered that Slug likely functions as a safeguard against age-related decline of breast stem cell function. Findings from the new study were published recently in Cell Reports through an article titled “Loss of Slug Compromises DNA Damage Repair and Accelerates Stem Cell Aging in Mammary Epithelium.”

“These findings help us understand how Slug functions in normal breast tissue and how it may function in breast cancer,” explained senior research investigator Charlotte Kuperwasser, PhD, professor of developmental, molecular, and chemical biology at Tufts University School of Medicine. “Slug is overexpressed in a subtype of breast cancer called basal-like breast cancer. If Slug is also critical for DNA damage repair mechanisms in basal-like breast cancers, it might increase the attractiveness of Slug as a therapeutic target.”

The main function of stem cells is to replenish tissues and to do so, stem cells need to stay healthy. One of the most important ways stem cells do this is by efficiently repairing damaged DNA, as unrepaired damage can lead to mutations in DNA that disrupt normal stem cell behavior. Upon detecting DNA damage, stem cells activate checkpoints to prevent replication of damaged cells, and they only regain regenerative activity after damaged DNA has been properly repaired.

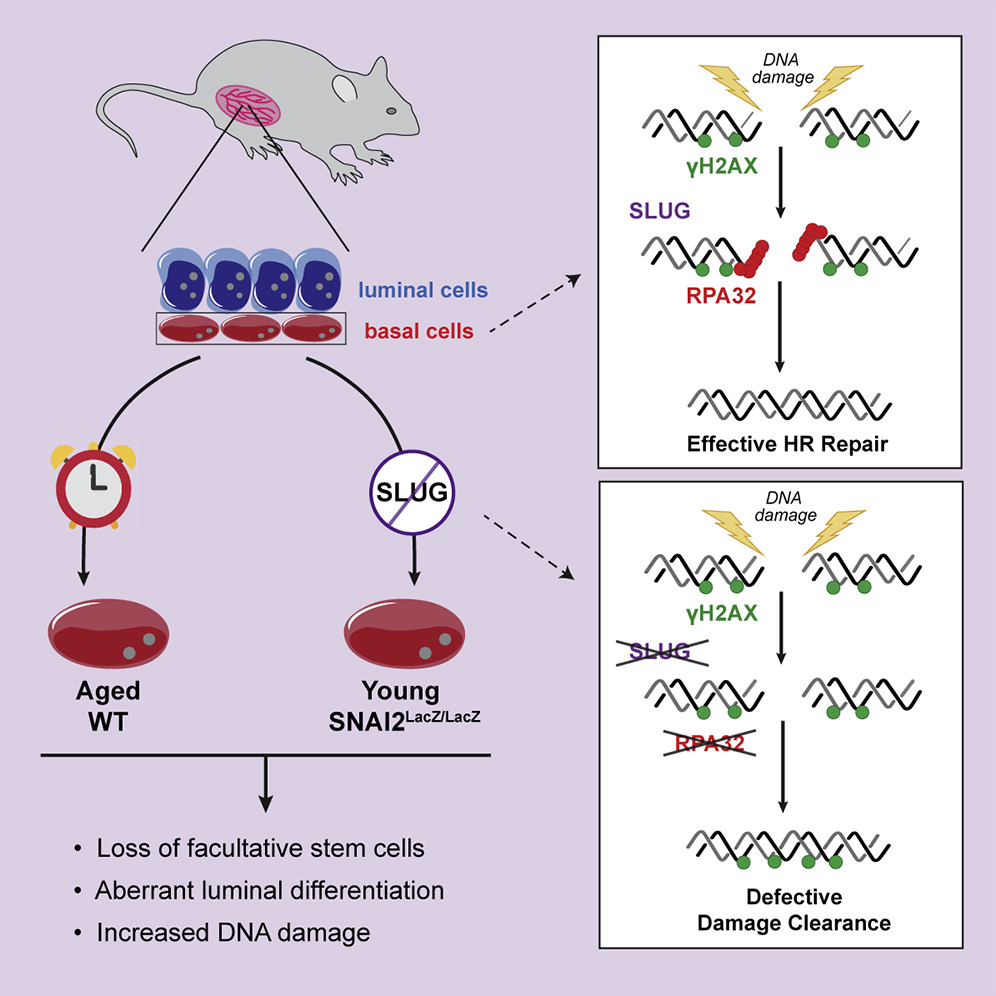

Specifically, the researchers found that Slug deficiency in human breast cells prevented the recruitment of key proteins that are required for repairing DNA. This function of Slug appears to be independent of its role in regulating gene transcription.

“We showed that Slug facilitates efficient execution of RPA32-mediated DNA damage response (DDR) signaling,” the authors wrote. “Slug deficiency leads to delayed phosphorylation of ataxia telangiectasia mutated and Rad3-related protein (ATR) and its effectors RPA32 and CHK1. This leads to impaired RAD51 recruitment to DNA damage sites and the persistence of unresolved DNA damage. In vivo, Slug/Snai2 loss leads to increased DNA damage and premature aging of mammary epithelium.”

The Tufts researchers have yet to determine whether breast cancer cells utilize Slug’s DNA damage repair function, but their current study did make a connection between Slug’s multifaceted roles in breast tissue and another biological process: aging.

As stem cells age, their ability to replicate and repair DNA damage decreases. The team found that breast tissue from aged mice had higher levels of DNA damage and lower stem cell activity. Importantly, these characteristics were also found in Slug-deficient breast tissue from young mice. The observation of these characteristics both in aged tissue and in young Slug-deficient breast tissue strongly suggests that Slug function is disrupted during aging. The precise mechanism of how that function is disrupted is still being investigated by the team.

“Our data point towards Slug acting as a safeguard against breast tissue aging, as it promotes both stem cell activity and efficient DNA damage repair, which are disrupted in aged breast tissue,” remarked co-first author Kayla Gross, PhD, who did this work as part of her dissertation at the Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences at Tufts.

“But these ‘fountain of youth’ properties of Slug are certainly a double-edged sword. Breast cancer cells may keep themselves up and running by co-opting the stem cell activity and DNA repair activity of Slug. What will be most important going forward is understanding how Slug is regulated. How do aged cells turn off its functions? How do breast cancer cells turn them on?” Gross concluded.