May 1, 2008 (Vol. 28, No. 9)

Viren Mehta Pharm.D.

Eric Snyder

Political Interest and Physicians’ Need to Drive Down Costs Could Create a Sizable Segment

The high cost of prescription drugs is a hot topic in this year’s U.S. presidential election and is likely to remain a priority to address in the next administration. With prices for treatments like Erbitux or Avastin exceeding $50,000 per year, political pressure is mounting to pave the way for generic follow-on versions of biologics.

Europe has already green-lighted the first biosimilars, as the European Medicine Agency (EMEA) terms them, such as Roche’s versions of erythropoietin. Expectations for biosimilars in the U.S. are increasing as the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) introduced by Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton, works its way through Congress. This legislation would create an approval path, and we could see the first follow-on biologics in the U.S. by 2011.

This market segment, estimated at $43 billion in 2006, may be safe for several years, but the coming impact to the industry could be significant. By 2013, at least 10 branded biologics with total sales of $15 billion will be generic and prime targets for genericization.

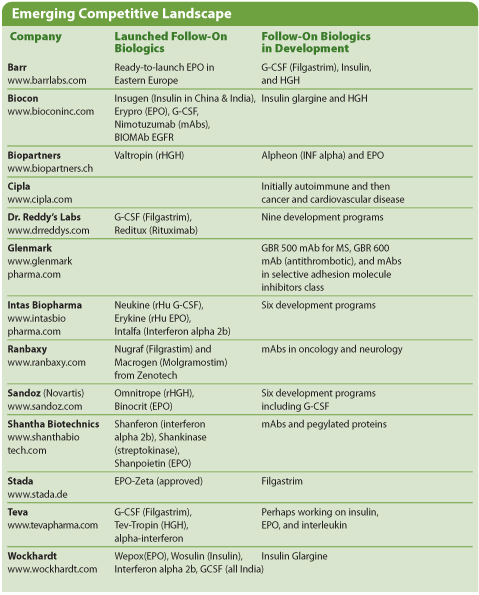

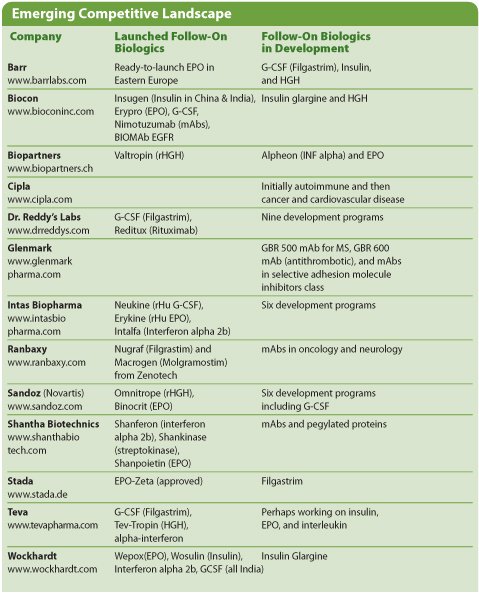

The cost advantages of overseas generics players such as Teva, Wockhardt, and others will amplify the effect of bio-generics.

Regulatory Landscape

The European Commission approved biosimilar legislation in 2004 and has been working proactively to develop and clarify regulatory paths and scientific guidelines with the EMEA. Europe approved their first biosimilar in 2006—Sandoz’ Omnitrope, a human growth hormone follow-on to Pfizer’s Genotropin. In September 2007, Sandoz’ version of EPO was also sanctioned in Europe.

More importantly, the EPO from Sandoz will receive the same international nonproprietary name (INN) as Amgen’s original Epogen, erythropoietin (EPO) alpha. This should make it interchangeable with the original at the pharmacy. In contrast, Stada has a biosimilar EPO that received the INN of erythropoietin zeta and is not interchangeable without physician consent.

The U.S. currently lacks a regulatory path to approve follow-on biologics, although this is a key issue for the Congress and Senate as well as part of the larger healthcare discussion in the current presidential election.

Emerging Competitive Landscape

Two competing proposals have been submitted to Congress, one by Henry Waxman, a Democrat favoring the generics industry, and the other by Jay Inslee, a Democrat favoring the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. Waxman’s bill provides for follow-on substitution of branded biologics and offers no data exclusivity. In contrast, Inslee’s proposal offers no substitution and 14 years of data exclusivity.

In June, a balance was struck when the Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions passed the BPCIA. The bill allows for a clear path for approval, some degree of substitution, and 12 years of exclusivity. Further, it gives FDA the ability to decide on the requirements for getting the go-ahead.

While there appears to be support for the compromise bill, it has not yet been voted on by the full Senate or House. Indeed, it may undergo substantial revisions as it is assessed by other committees. Key issues remain to be debated, including approval requirements and clarification of patent concerns. These deliberations and potential modifications are likely to keep the bill from a broad vote until the second quarter.

If the House and Senate approve legislation this year or even in 2009, it could pave the way for follow-on biologics approval in 2011.

The Market in Five Years

Predictions as to where the market will be in the next few years vary with the industry’s, physicians’, and global perspectives.

One representation of the former is a recent white paper from Henry G. Grabowsk, Ph.D., and colleagues at Duke University. Dr. Grabowski, director of the program in pharmaceuticals and health economics, estimates a minimal effect of biosimilars. He draws on the history of complex small-molecule generics and FDA’s 2006 approval of Sandoz’ Omnitrope. While the agency did allow Omnitrope to enter the U.S. market, it is not viewed as therapeutically equivalent to Genotropin and is thus not a true generic that can be substituted at the pharmacy.

Dr. Grabowski estimates that if follow-on biologics manufacturers need to market their products in a similar manner as Sandoz and there is a high fixed cost of manufacturing, then follow-on biologics will be priced at a relatively modest 10–30% discount to the originator price. At this value, physicians may be hesitant to stray from tried-and-true branded products and follow-ons will be used in 10–40% of patients. BIO has enthusiastically endorsed this view and posted Dr. Grabowski’s publication on its website.

The scenario painted by Dr. Grabowski may not fully factor in the high degree of physician frustration with current biologic prices nor the impact of the global economy. Leading oncologists have spoken publicly against the pricing of biologics and the fact that many patients, even with insurance coverage, have difficulty affording the required $10,000–20,000 copay.

Leonard Saltz, an oncologist from Memorial Sloan-Kettering who helped develop Erbitux, said that ImClone “made a real mistake in their pricing.” His view appears to be widely shared. In a Decision Resources survey at the 2007 ASCO meeting, 60% of oncologists were “extremely willing” to prescribe biogenerics of leading cancer medicines within six months of release. Thus the 40% peak share estimated by Dr. Grabowski appears low.

Taking a global perspective, we see that a branded biologic priced at $10,000 a year may cost just $2,000 to manufacture in the U.S. or Europe. In contrast, companies in our Indian generics universe have gross margins closer to 50%. This means that an Indian generics company could enter the market, manufacture the same product, and be content to sell it at $4,000-5,000, a 50–60% discount. For example, last year Dr. Reddy’s launched a follow-on to Roche’s Rituxan/Mabthera in the Indian market at Rs. 20,000 per vial, or approximately $505, a 50% discount to Roche’s price in India.

With additional entrants and lower-cost manufacturing, prices could be driven down further. For example, Wockhardt recently invested $38 million to build a facility capable of manufacturing 15% of the worldwide supply of biologics.

Global competition and economy of scale could allow physicians, patients, and hospital administrators to get FDA-okayed-equivalent therapies and save themselves half the cost or more. If that happens, follow-on biologics could receive top-tier placement on formularies or even fail-first treatment, as has happened with many small molecule generics. On cost alone, without marketing, follow-on biologics could achieve dominant market share.

Yet, even with the first launch of biosimilars in Europe and a regulatory path taking form in the U.S., we remain several years from follow-on biologics/biosimilars emerging as a major force in the industry.

That said, the investments being made now to scale up manufacturing of follow-on products in conjunction with the evolving regulatory environment is poised to create a sizeable sector. Companies that are investing today in large-scale, low-cost manufacturing are likely to have a sustainable advantage in this sector in the years to come.

—

Viren Mehta, Pharm.D. ([email protected]), is managing member, and Eric Snyder, Ph.D. ([email protected]), is an analyst at Mehta Partners. Web: www.mpglobal.com. Phone: (212) 343-4300.