![Although the two angiotensin II receptors are thought to be very similar, an X-ray study showed clear differences in the pockets where the receptors bind to drug-like compounds. This illustration shows details in the pocket structures of AT2 (left) and AT1 (right). Additional findings suggest that AT2 makes use of an alternative signaling pathway, one not reliant on intracellular G protein or arrestin. [Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory]](https://genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/137069_web1122331761-1.jpg)

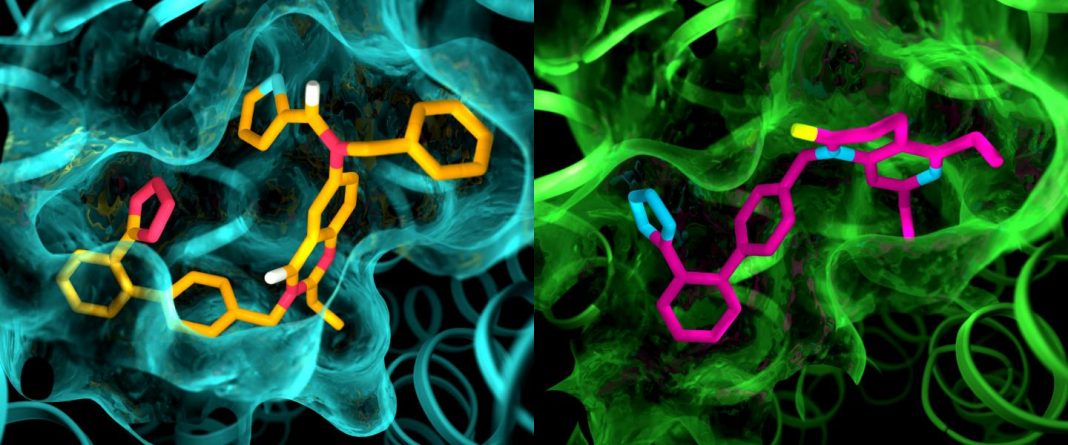

Although the two angiotensin II receptors are thought to be very similar, an X-ray study showed clear differences in the pockets where the receptors bind to drug-like compounds. This illustration shows details in the pocket structures of AT2 (left) and AT1 (right). Additional findings suggest that AT2 makes use of an alternative signaling pathway, one not reliant on intracellular G protein or arrestin. [Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory]

Of the two sister angiotensin II receptors, one has become a reliable drug target, while the other has remained something of a puzzle. The reliable one, known as AT1, has inspired many of the hypertension medications currently on the market. The strange one, known as AT2, has been studied frequently, but its function is still unclear.

To tease out AT2’s inner workings, scientists have undertaken a detailed structural study. They presented their findings April 5 in the journal Nature, in an article entitled, “Structural basis for selectivity and diversity in angiotensin II receptors.” According to the scientists, their work opens doors to potential new therapies to control cardiovascular disease and pain.

“To identify the mechanisms that underlie the differences in function and ligand selectivity between these receptors, here we report crystal structures of human AT2R bound to an AT2R-selective ligand and to an AT1R/AT2R dual ligand, capturing the receptor in an active-like conformation,” the article’s authors wrote. “Unexpectedly, helix VIII was found in a noncanonical position, stabilizing the active-like state, but at the same time preventing the recruitment of G proteins or β-arrestins, in agreement with the lack of signalling responses in standard cellular assays.”

“AT2 does not work through canonical signaling pathways for GPCRs,” said one of the paper’s co-authors, Vsevolod Katritch, Ph.D., assistant professor of biological sciences and chemistry at USC Dornsife. “It doesn't activate a G protein and it doesn't work through arrestins.”

In most cases, G proteins and a group of proteins called arrestins interact with a cleft that opens up on the intracellular side of GPCRs upon activation. When a stimulus triggers the GPCR from outside the cell, the GPCR activates a G protein or arrestin within the cell, which then relays the signal to other proteins in the cell, and so on, in something akin to a game of molecular “telephone.” AT2, however, works through some other, currently unknown mechanisms of relaying the signals into the cell.

To better understand AT2, Katritch along with Vadim Cherezov, Ph.D., professor of chemistry, biological sciences, and physics and astronomy at the USC Dornsife, and other scientists at the Bridge Institute collaborated with researchers at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC), Arizona State University and Merck & Co. to clarify its structure.

The team bound two different molecules to AT2 as part of the process. The first molecule adhered only to AT2. The second bound both AT2 and its close relative, AT1.

![Researchers use powerful X-rays to reveal molecular structures at the site where drug compounds interact with cell receptors. These structures help point the way to designing medicines of the future. [Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory]](https://genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/137068_web1961792271-1.jpg)

Researchers use powerful X-rays to reveal molecular structures at the site where drug compounds interact with cell receptors. These structures help point the way to designing medicines of the future. [Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory]

The scientists then used X-ray crystallography at a powerful X-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) source to determine AT2's structure. The SLAC facility, which hosts the world's first hard XFEL, known as the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), was key to uncovering these new findings.

“This kind of room-temperature measurement on interesting membrane protein targets is something that LCLS is well-suited to perform,” said SLAC staff scientist Mark Hunter, Ph.D. “Membrane proteins remain elusive targets for high-resolution structural studies, and researchers can spend many years trying to obtain crystals that are well ordered and large enough to use at conventional light sources.”

The X-ray crystallography results produced a trio of surprises.

First, even though the two binding molecules were designed to inhibit and neutralize AT2, the researchers found that both seemed to do the opposite.

“These molecules were derived from AT1 receptor blockers; therefore it was unexpected to find that they transform the AT2 receptor in an active-like state,” Dr. Cherezov said.

The researchers also saw that a helical section of the AT2 protein blocked the site where G proteins and arrestins normally interact.

In most GPCRs, this flap of protein, known as helix VIII, lies along the inner surface of the cell membrane. “But in AT2, it's down, physically blocking the G protein and arrestin-binding site,” Dr. Cherezov said. “That may explain why nobody could detect signaling through G proteins or arrestins when studying AT2.”

Finally, the crystal structure revealed previously unknown differences between the sites where small molecules, such as drugs, bind to AT2 and AT1.

“The idea was always that receptors that are closely related and are activated by the same signal peptide should have similar binding pockets, so most drug discovery efforts for AT2 focused on the same chemical scaffolding that previously worked for AT1,” Dr. Katritch said. “The startling differences between AT2 and AT1 ligand pockets that we see now will help us to have a fresh start on designing smaller, more drug-like molecules that are tailored to fit the AT2 receptor, which could set the drug discovery process in a different direction.”

While noting that further research is needed, Dr. Cherezov said the current discovery is an important first step both to better understanding of similar atypical GPCRs and to potential new therapies.

“The structure gives us the first clue of what's happening on a molecular level,” he said. “We need to study further to really understand what other proteins it interacts with and how AT2 propagates signals in the cell.

“This information then could be used to design selective drugs that specifically target AT2 and not AT1 or other GPCRs,” he explained. That may be good news for patients coping with chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and pain.